'Alifba is an icon of Tatar culture'

National Library of Tatarstan proposed to make a pivot to the global Tatar world of writing

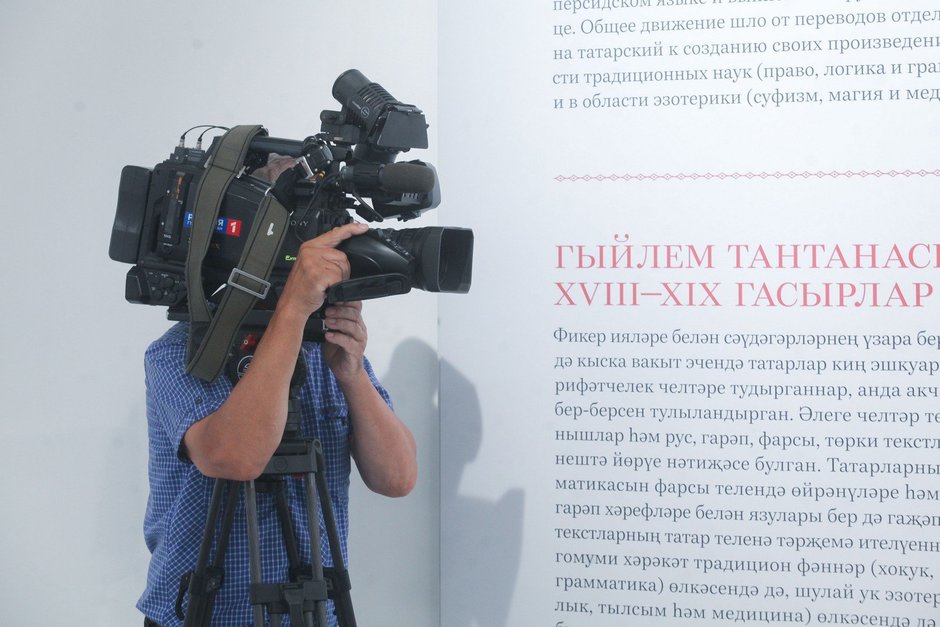

The exhibition 'Global World of Tatar Literature' is opening in Kazan at the National Library — this is the first great experience of the main book depository of the republic in this field. The project is dedicated to the Year of Native Languages. The exposition was evaluated by the correspondent of Realnoe Vremya.

Mapping, digital calligraphy, and the art of commenting

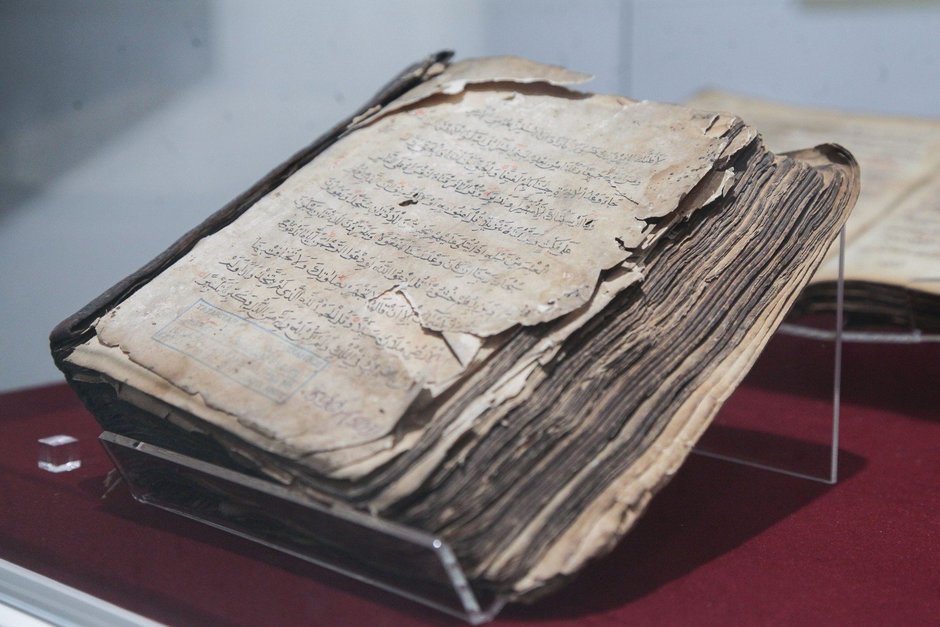

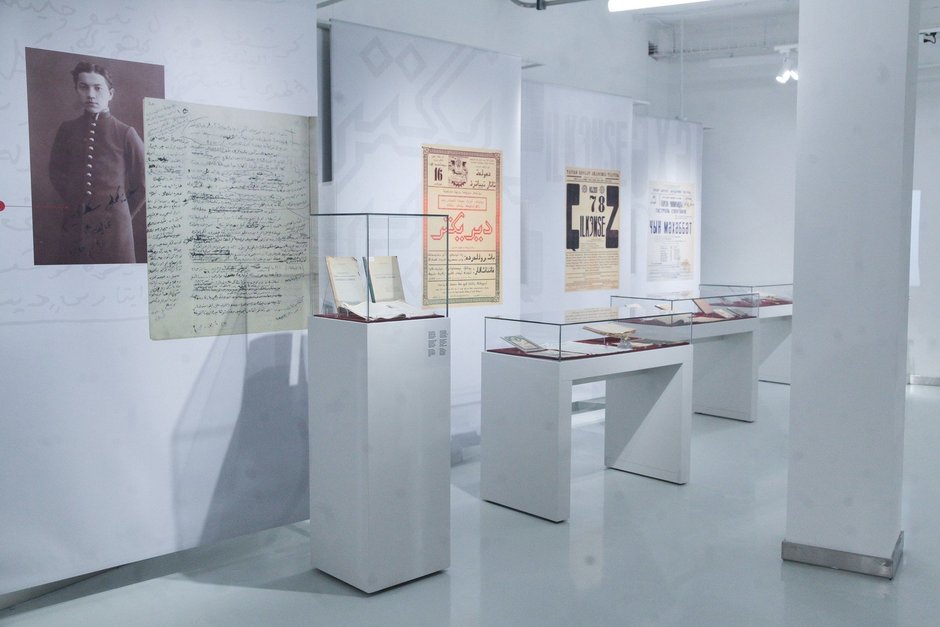

“The National Library has never withdrawn so many materials from the collections — these are 100 documents that have been stored here since the 20th century," said its director Madina Timerzyanova.

Also, the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Tatarstan, National Museum of the Republic, N.I. Lobachevsky Scientific Library, Tatarstan STRBC, and the University of Amsterdam helped in the preparation of the exhibition.

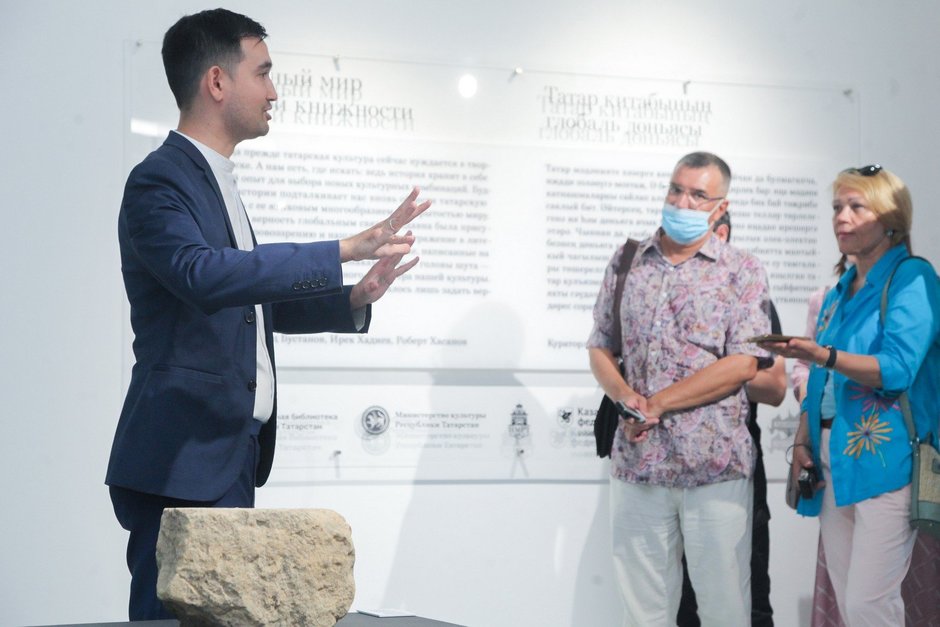

The exhibition has three authors. Alfrid Bustanov, appointed deputy director of the Sh. Mardzhani Institute of History at the beginning of the year, who devoted himself to the study of Turkic manuscripts. In 2019, he began working on the project “Identity of a Muslim in Imperial and Soviet Russia” within the framework of a grant from the European Union. Irek Khadiyev, deputy director of the library for scientific work, expert on local funds. And Robert Khasanov, head of the Smena project, who was responsible for the material implementation of ideas into life.

The star of the press show was Bustanov, who told reporters in detail about the exhibition. The exhibition is planned to have an audio guide with the voice of Alfrid. However, the organisers assure that there are so many inscriptions, explanations and texts at the exhibition that you can learn a lot yourself. It opens with the projection of inscriptions on graves on white slabs — they were made with a stylus by young calligrapher Ayzat Mingazov. He says that it took up to a day and a half for each inscription, so then people saw Arabic letters on their faces. These exhibits are related to the book by Shigabutdin Mardzhani “Mustafad al-akhbar fi ahval Kazan va Bulgar” (“A storehouse of information about the affairs of Kazan and Bolgar”), in which he literally tries to find his roots through the stones found on the territory of the Arkhiereyskaya dacha.

“Here every visitor will find not a right answer, how to understand everything, but will find questions that concern any person who lives in our country," Bustanov began. “Who am I, where are we all going, what is important in our past, what will we take from the past, what can we teach our children.”

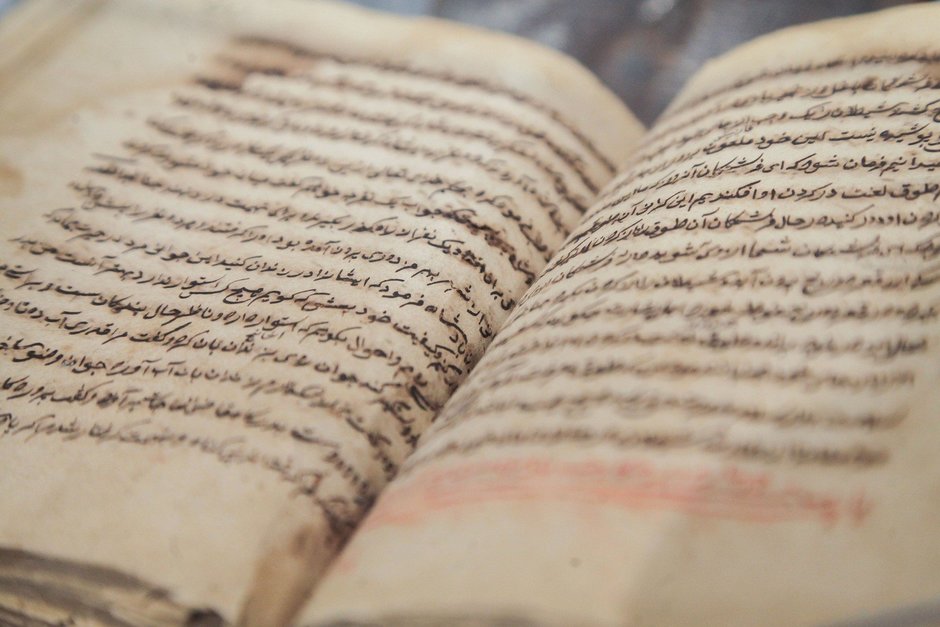

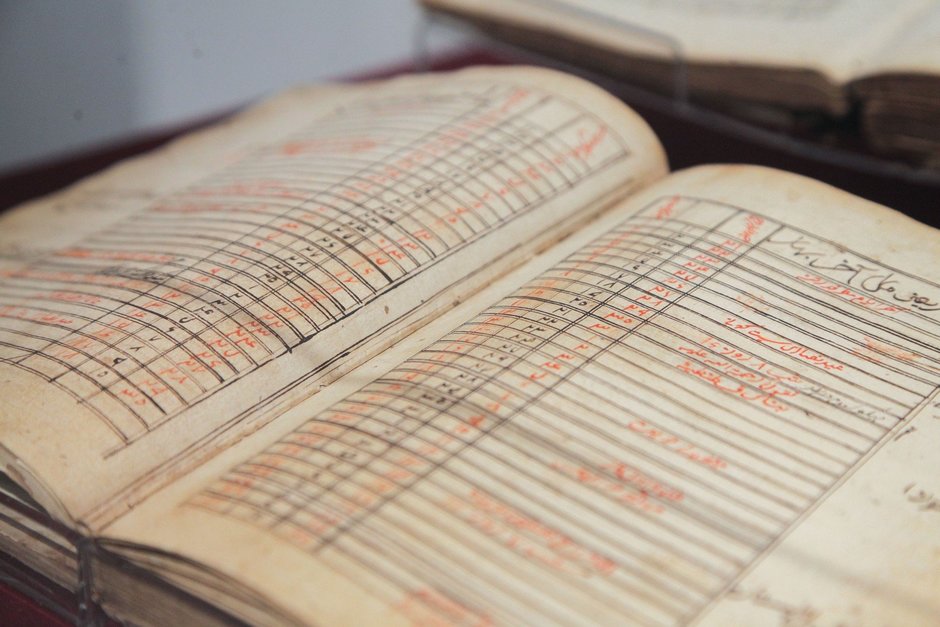

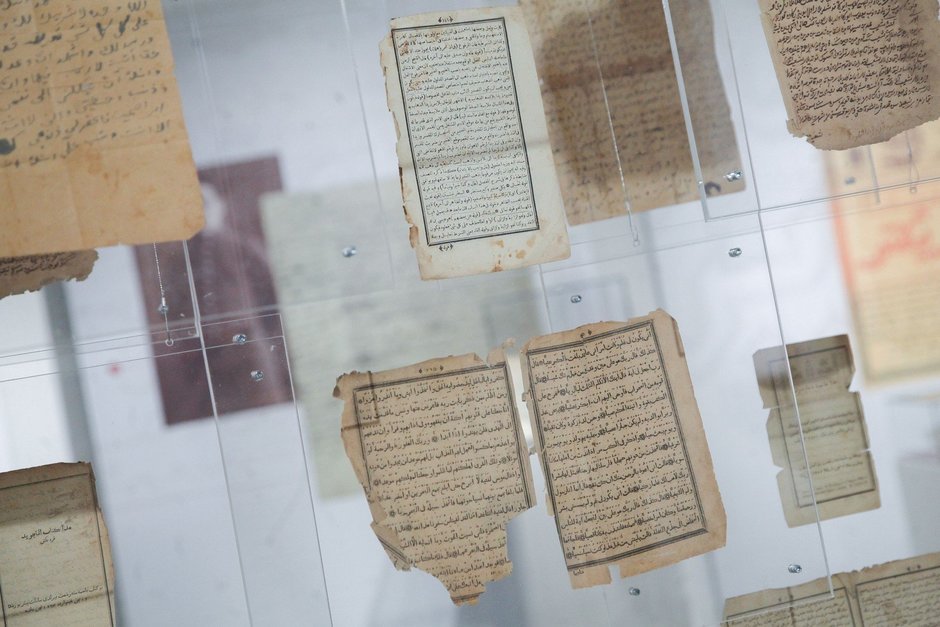

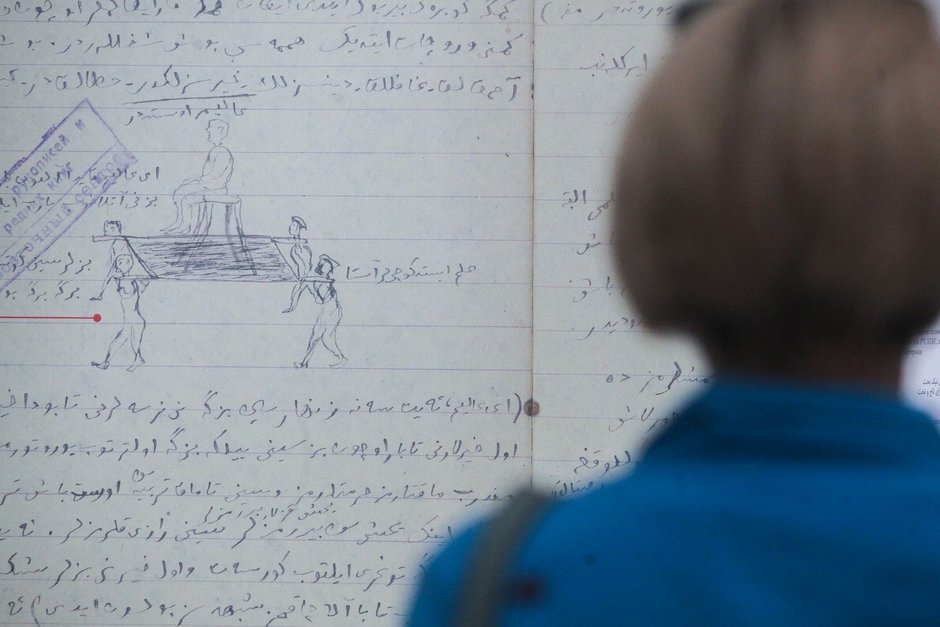

At the same time, each section is not only a demonstration of continuity, but also gaps, dramatic fractures, the scientist says. After the tombstones, the viewer proceeds to a video projection with coins, and then to a large number of enlarged images with texts and showcases with manuscripts. To be honest, the first one is more impressive, because there is some kind of discovery in each. For example, here are Persian texts — but they were copied by the Tatars on dutch paper. These patterns should be a part of modern life, says Bustanov, why not return them to our costumes?

And then he shows the manuscript, on which, according to one of the theories, the date 1607 is written in Russian letters. This is followed by an installation with several main types of Arabic graphics — this place should become the main instaspot.

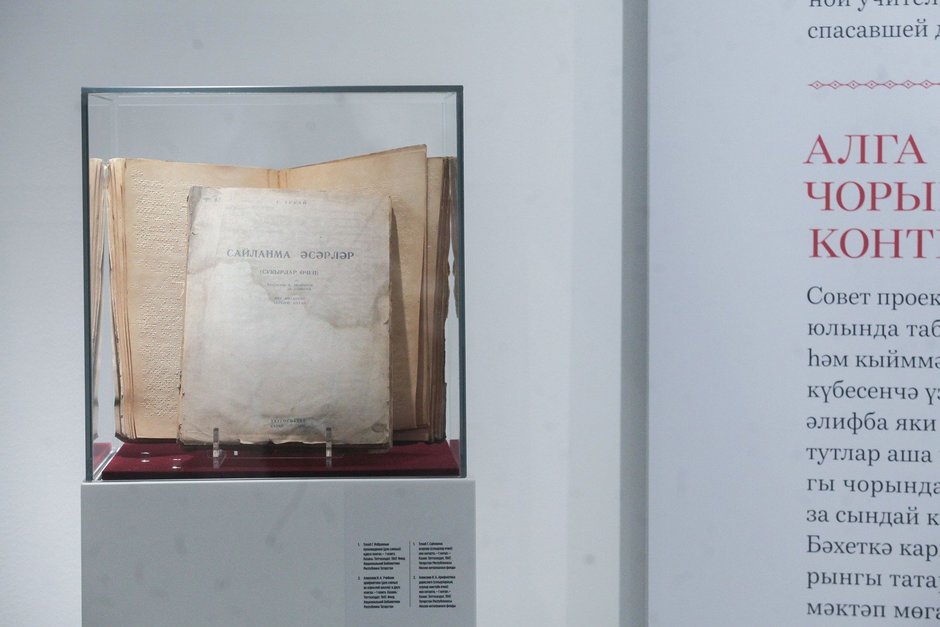

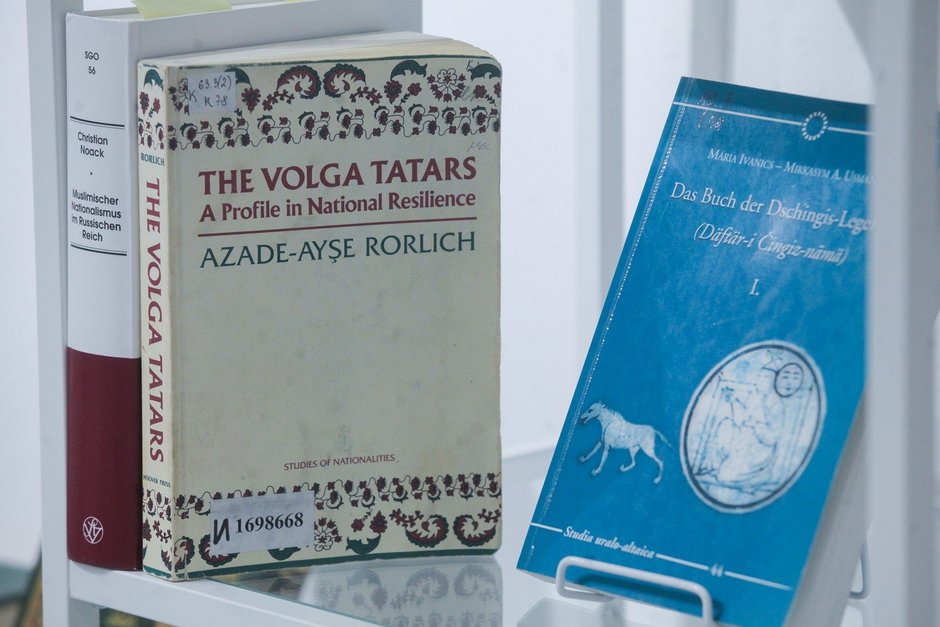

Before the 20th century, we are greeted by several shelves with books that demonstrate the interest of scientists in our manuscripts. They are in foreign languages, whether it is an English book about the Bukhara prestige in the Tatar culture of the 20th century or a Uyghur book about the history of Tatar madrassas in Xinjiang.

Turn around and look!

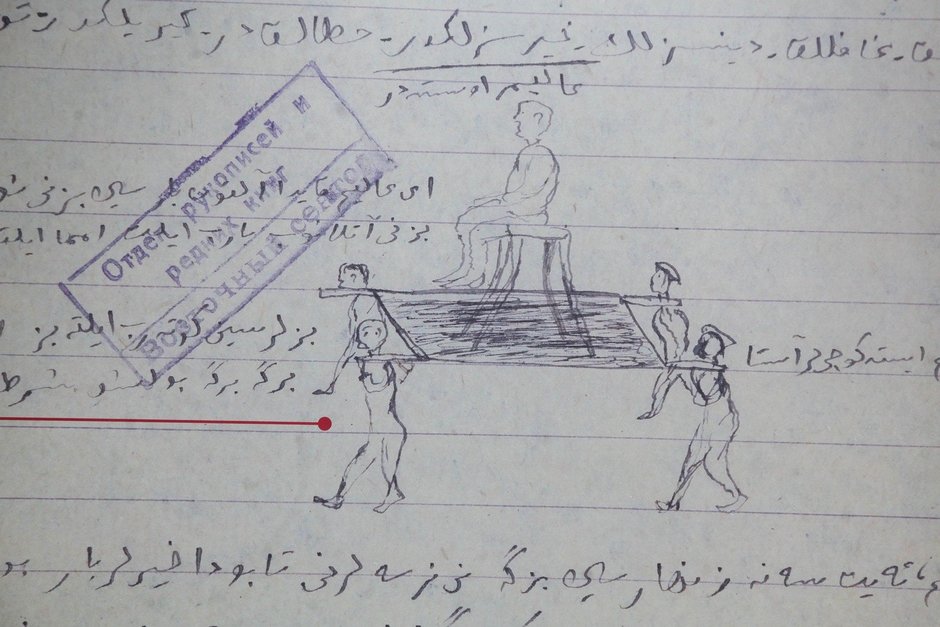

The 20th century is the history of the reform of Muslim education, the transition from Arabic letters to Latin and Cyrillic, which quickly replaced each other in the first half of the century. Bustanov emphasises that this was not a simple transition, the story is more complicated, and it sometimes changed the fate of people.

Here is Galimzhan Sharaf, one of them. When he was 20 years old, he wrote the history of the Golden Horde, was one of the authors of the Idel-Ural project. And after his imprisonment in the camp, he is already engaged in the “proletarisation of the language” and preparing for the Latin alphabet.

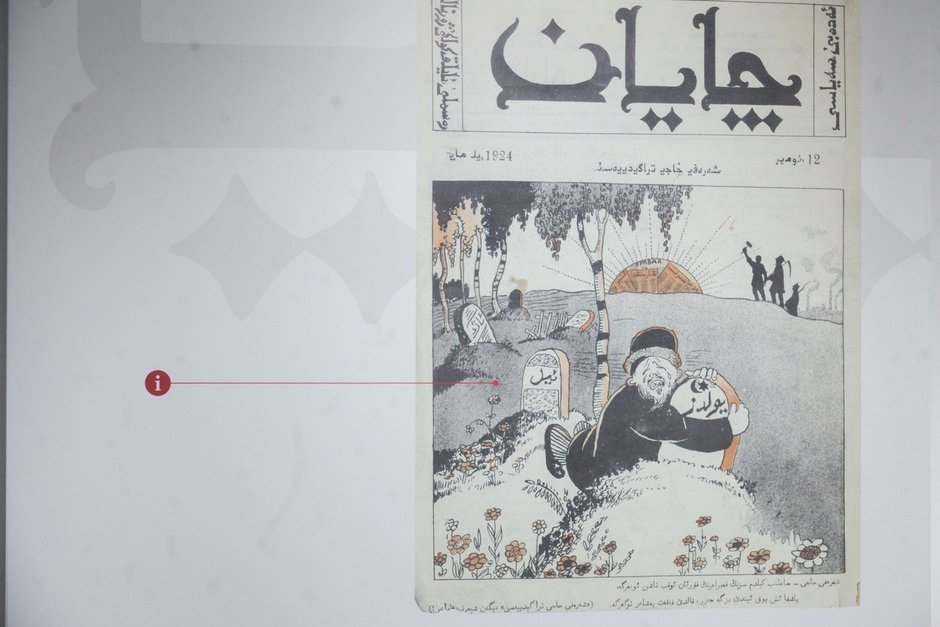

In this situation, many artifacts of the past change their meaning. A cartoon from the Chayan magazine shows an old man hugging tombstones with Arabic inscriptions, while the sun of a new life rises in the background. Now this picture looks different — it is no longer a sunrise, but a sunset.

The exhibition also offers to look at alternative variants of the alphabet development: this is the reluctance of some people to switch to the Cyrillic alphabet (Realnoe Vremya published excerpts from the diaries of artist Baki Urmanche — he originally wrote in Arabic) or the conscious choice of the Latin alphabet by individual diasporas (as was the case with the Finnish Tatars).

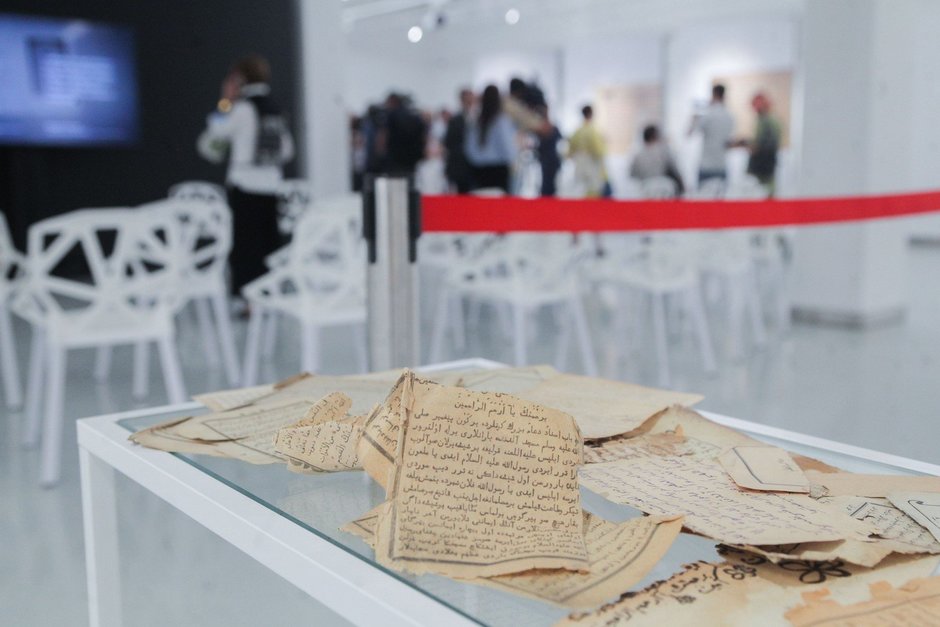

Bustanov suggests looking at the centre of the exhibition — there are, wrapped in glass, hanging fragments of various documents, books, which people voluntarily got rid of in Soviet times.

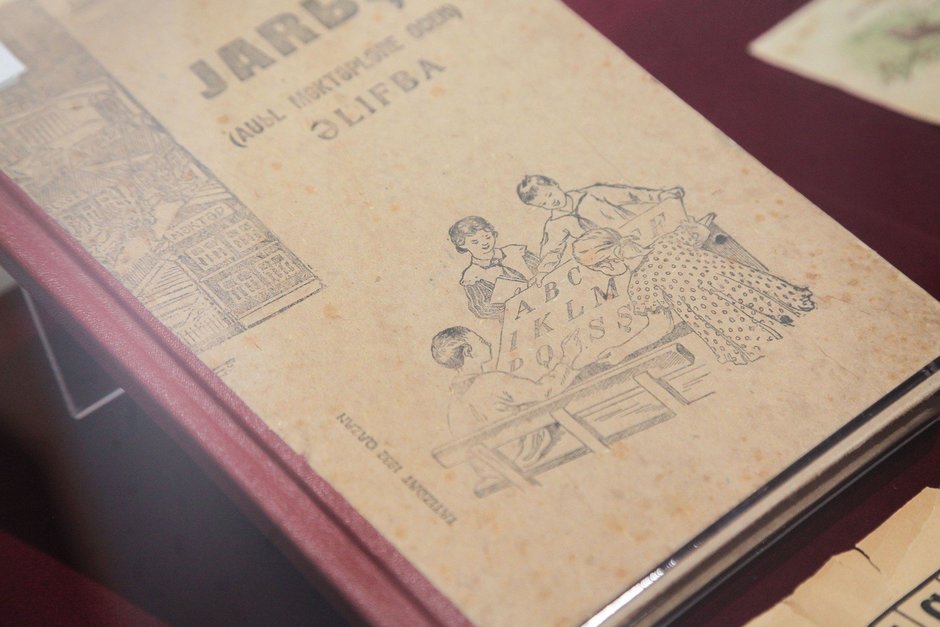

After that, he approaches the image of alphabet book Alifba is now a symbol of the struggle for the Tatar language.

“When Alifba appeared, there was a canon of Tatar culture that we know," Bustanov notes a little ironically, “which we associate with Tatar culture.”

It is known that the young scientist is an apologist for the study of pre-revolutionary culture, who is not close to the enthusiasm about the Jadid movement with its appeal towards Europe and the glorification of Soviet Tatar culture. At the press show, he demonstrates this by standing almost point-blank with the image of the alphabet — this is how we see our culture.

“But if you turn around and look here," here he turns towards the rest of the exhibition, “and we see that we have access to a huge cultural repertoire that has been lost in the corners of history, but we can grab it and update it. Alifba is an icon of Tatar culture.”

As promised by the deputy director of the library, Tabris Yarullin, it is planned that the exhibition will become a platform for a parallel programme. Firstly, this is a new season of the laboratory for deciphering manuscripts (we have published some of them), as well as, for example, participation in the media art festival Nur, which will be held in the autumn.

The exhibition is open daily from 11 am to 8 pm, except for the last Monday of each month. It is open until November 2021.