Budget grows, public debt reduces, but Russians don't feel better

Realnoe Vremya draws economic conclusions of 2018 in Russia

It's easier to call economic results for 2018 contradictory. On the one hand, the situation in state finance improved amid favourable circumstances; in addition, authorities set important social tasks during the year. At the same time, citizens didn't start feeling better: recovery of their incomes ended with the presidential election, while 2019 promises to be tougher than 2018. Realnoe Vremya tells the details.

Sanctions work. For sure now

2018 was the year when everyone made sure first-hand that sanctions might make feel notably uncomfortable. The USA hit several Russian businesspeople, top managers and functionaries in April. Particularly Oleg Deripaska, Igor Rotenberg, Viktor Vekselberg, Suleyman Kerimov, Andrey Kostin as well as companies related to them were blacklisted.

The news about the sanctions ruined the Russian stock exchange market, but it was just the beginning. Fearing escalation, foreign investors began to get rid of Russian assets. The share of non-residents in the market of federal bonds reduced from 34,5% in March to 24,7% in November, which obviously didn't favour the ruble.

As the sanction rhetoric became stricter, the tension went up. At a moment, emotions became the main rate generating force having suppressed all objective factors (including high oil prices).

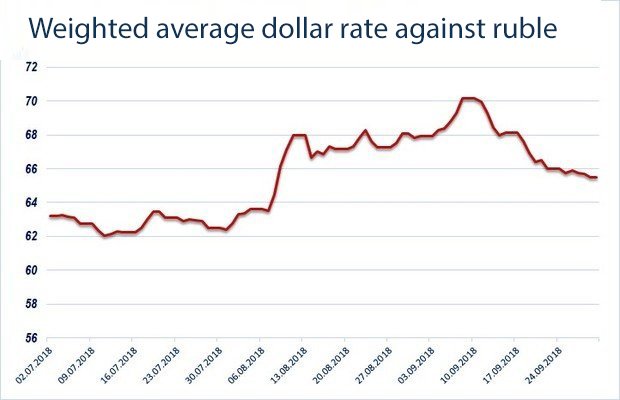

The peak was in the third quarter. An average dollar rate, which was 62,8 rubles/$, rose to 66,4 rubles/$ in August and reached 67,6 rubles/$ one month later. The dollar crossed the psychological threshold of 70 rubles in the first decade of September.

The third quarter was unlikely to be successful for Sberbank – once the most expensive Russian company (now Rosneft holds this status). It lost about one-tenth part of its market price for five months. Due to the threats, a common Sberbank share's price fell from 210 rubles as from 1 August to 186,5 rubles on 28 December.

Of course, not only the sanctions but also circumstances that came together influenced the ruble rate. However, Denis Gorev from General Invest says sanctions played the key role in the outflow of Russian assets.

At the same time, we can't say Russia became a ''toxic'' market for foreign investors, Gorev says: ''If we look at the CDS of Russian euro bonds, it's considerably lower than the level when Russian assets were really considered as toxic – after the annexation of Crimea. This is why it's early to talk about a mass outflow of investors at the moment – this hasn't happened yet.''

Regions breathed easily…

The consolidated budget of Russia had a surplus in 2018 for the first time in five years. Official data for 2018 haven't been published yet. But according to interim performance, another result is unlikely.

The departure was partially situational. An average Urals price was 40% higher in January-September per barrel than in the analogous period in 2017, oil crude export grew at corresponding paces (+38% year on year). Feedstock profits gave an impulse for growth in incomes from taxes paid by businesses. At the same time, they allowed the federal government to distribute interbudgetary transfers more generously.

This became support for Russian regions: in nine months, there were just 16 regions with a budget deficit, though the number was twice bigger one year ago – 31. The total surplus of consolidated regional budgets in January-September amounted to 754bn rubles.

In her recent Economic Situation Monitoring, Natalia Zubarevich writes that Sevastopol, Khakassia, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karelia augmented their incomes faster – it's the regions that received more transfers. The fall in incomes (by 4-9%) was observed only in two Russian regions: Mordovia and Mari El.

Chief economist at Expert RA Anton Tabakh believes that regions will maintain good budget indicators in 2019 too, though circumstances won't be as favourable as before.

Chief economist at Expert RA Anton Tabakh believes that regions will maintain good budget indicators in 2019 too, though circumstances won't be as favourable as before.

''Tax payments are usually quite inertial, especially income tax. This is why the reduction in export incomes (only in the gas and oil sector) will be seen only in the middle of the year. This year will be more complicated than 2018, undoubtedly. But the positivity will remain with the basic scenario. Moreover, a part of regions will get money for national projects by the end of the year – incomes from their fulfilment,'' Tabakh says.

The situation with regional public debt became a bit better than last year. Its total volume reduced by 86,5bn rubles during the year (from 1 December 2017 to this year's December). The number of regions with too many loans shrank too. At the same time, troubled regions didn't start feeling better (Mordovia remains major among them) – the debt load in some of them only increased during the year.

''The situation with the regions' public debt is the following: those who felt good started to feel better, those who felt bad started to feel worse,'' Anton Tabakh notes.

… But population didn't start feeling better

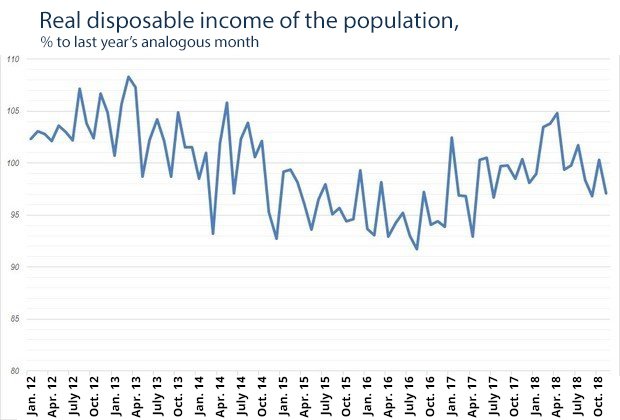

Early in 2018, the Russian State Statistics Service began to report that the lasting fall in real income of the Russians, which was 38 months non-stop, finally ended. As it became clear later, it was early to celebrate the victory. In November, the service calculated incomes earned last year, as a result of which data for 2018 also changed.

According to the new data, the growth in real incomes turned out smaller (compared to the first estimate). In addition, it was more discontinuous. The population's income increased relatively rapidly only before the pre-election cycle ended – from February to April. After the election, the Russian State Statistics Service detected either less impressive growth or fall. In general, real disposable income grew just by 0,4% in January-November, excluding last year's one-time payment to pensioners.

What's more, the number of regions where the population goes on becoming poor grows month after month: a reduction in incomes was seen in the majority of Russian regions during 10 months last year – 60 out of 85.

Kremlin leads the country to a bright future

All efforts of the government in the next years will be put to achieve new strategic goals – their full list is available in Vladimir Putin's decree No. 204 as from 7 May 2018.

The supertask of the May Decree might be briefly described as a general improvement of the citizens' quality of life. For instance, the government must annually provide at least 5 million families with better living conditions, increase life expectancy to 78 years by 2024 and accelerate the country's technological development.

The most notable clauses of the May Decree are about economic potential and solution of social problems. Firstly, Russia is to be in the top 5 countries with the highest GDP per capita in the next six years (including purchasing power parity). Secondly, the poverty level in the country must reduce twice during those years.

… But road promises to be tough

In the experts' opinion, authorities can achieve the goal of reducing poverty, which went up after the crisis in 2014. But ambitions linked with joining the top 5 biggest world economies seem too high to many people: to do it, greater economic growth is needed, which is now seen only in official forecasts. The World Bank has just recently claimed Russia might become the fifth world economy, but four years later.

Even the traditionally optimistic Russian Ministry of Economic Development doesn't hope for a ''breakthrough'', which Putin talked about, in the next one-two years. The International Monetary Fund claimed in May 2018 that Russia's development prospects ''remained weak'': ''With the projected growth rates, the country would lag behind peers in Eastern Europe and convergence with advanced economies would not take place.''

2019 will be tougher than last year

How does Russia enter 2019? The rise in VAT together with other factors has been augmenting prices for several months. The Central Bank forecasts inflation will increase to 5-5,5% in the first half of 2019. This questions the growth potential of the citizens' real income – especially if we consider that the period of fast growth in salaries likely ended together with the election (the dynamics here was in a decline in October already).

Oil prices, which were at a high level during the most part of the last year, suddenly collapsed in December; some experts believe the return to last year's indicators was unlikely at the moment. Cheapening oil is an additional factor to put pressure on the ruble. In addition, the reduction in export incomes might weaken the economic growth, which is already weak, economist Sergey Khestanov said: ''There is no reason to panic, there is nothing to be glad about, either.''