What modern Bashkir prose is about: epic in a new way, Bashkortostan in the 90s and folk evil spirits

The work of young Bashkir writers was discussed at non/fiction№26 International Fair of Intellectual Literature

The trend for local literature has been breaking all popularity records for the third year. Readers are interested in learning not only about how people live in different regions of Russia but also immersing themselves in the history and mythology of individual peoples and ethnic groups. Bashkortostan has a rich cultural heritage where there is a literary tradition, folklore and history. Three Bashkir writers presented their debut novels at non/fiction№26 the International Fair of Intellectual Literature.

Growing up in the 90s

Elza Gildina's story The Goat Hurries to the Woods tells us the story of fifteen-year-old Lesya who is trying to find her place in life. The story is around the fate of a girl from Bashkiria who lives at the junction of eras. She rushes between the strict discipline of her grandmothers, the crime dramas of the outside world and her own inner world. Gildina creates a realistic atmosphere of the late 1990s where hopes, fears and everyday realities typical of the region are mixed.

The title of the story refers to an ancient proverb: “Don't rush, goat, into the forest — all your wolves will be.” “To my surprise, I learned that not everyone knows this proverb. And I thought that everyone knew it. The goat here is in a hurry to the forest, that is, to adulthood, to meet its dangers. She is warned not to rush, but she goes there anyway,” the author explained. This image permeates the entire plot: stubborn and independent Lesya enters a new stage of life, trying to find her truth.

Lesya is a difficult teenager with a categorical character. Her world is full of manipulation, fears and doubts. Lesya was raised by a strict grandmother, and, as Gildina said, “the strictest parents raise the most sophisticated liars.” The girl rushes between teenage complexes, jealousy and envy. She falls in love, experiences the pain of unrequited feelings. “As soon as a child ceases to be a child and becomes a teenager, trials begin: unrequited love, jealousy, envy. Try to pass this test,” the writer added.

At the same time, Gildina fills the narrative with realistic details. Bashkir culture, everyday habits and speech features become an important part of the narrative. “Speech distinguishes a person. If you live in Bashkiria or Perm, you will immediately see the peculiarities of the local speech. Or rituals — we bury dead Muslims according to customs: they are wrapped in a white cloth and buried on the same day. All this makes the region unique, but at the same time understandable to everyone,” said Gildina. This locality, according to the author, helps to preserve authenticity and at the same time remain accessible to any reader.

Interestingly, Gildina refers not only to Bashkir traditions, but also to the mythology of the Soviet era. “Lesya suddenly feels like one of the plaster statues is coming to life. These are the same statues that many saw in pioneer camps: a girl with an oar, a boy with a horn,” the author said. Lesya seeks solace in literature, which becomes her kind of “religion.” “My heroine has her own religion — literature. She loves Balzac very much,” shares Gildina.

The Goat Hurries to the Woods is both a local and universal story. Elza Gildina emphasised: “If you write about yourself, people will still understand, because everyone is alike. Even if you describe your experiences in Bashkiria, you will be understood in Moscow and Yekaterinburg. It is important to be honest with yourself.” The writer does not seek to demonstrate “Bashkir flavour” for the sake of fashion, but simply tells her story. But it is in this truthfulness that what many call the uniqueness of the book is born. “People note: after all, the story is colourful. These grandmothers, their words, their speech — all this distinguishes the place in question,” Elza added.

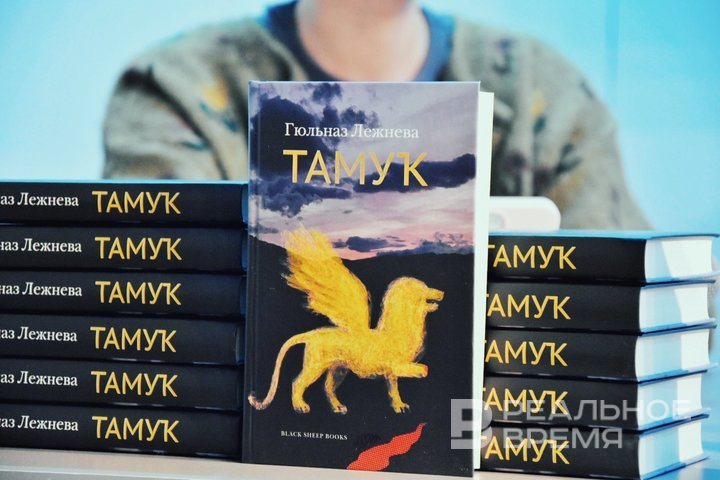

Bashkir epos and village realities

The novel Tamuk by Gyulnaz Lezhneva is an attempt to breathe life into the ancient Bashkir epic, combining it with the realities of a modern village. Lezhneva is not afraid of experiments, saying: “I brought the epic to life. We are talking here, and somewhere behind the walls this struggle between good and evil continues.” According to the plot, seven-year-old Naila sits down every evening in front of the TV, which has not worked for a long time. Ural and Shulgen, two opposing brothers from the epic Ural Batyr, appear in its ripples. This fantasy world becomes reality for the girl. “Almost all of my mythological elements are from Ural Batyr, Lezhneva shared. This connection with the epic is not accidental. The plot of the ancient tale is based on the struggle of Ural Batyr with chthonic monsters and evil forces. Lezhneva weaves these images into everyday life, creating the feeling that the heroes from the legends are always somewhere nearby.

Lezhneva opposes the opinion that the epic dies as soon as it is written down. On the contrary, she argues that it is through literature that we can preserve its relevance: “The epic has come to life. It is no longer a frozen text, but something that lives and changes along with the people.” In Tamuk, ancient motifs become universal. This is a story about the struggle between good and evil that does not depend on time. “Naila’s trials run parallel to those that her father faced,” Lezhneva explained.

But Lezhneva does not limit herself to describing the life, everyday life, and rituals of the village. She raises questions of religion and identity. “Bashkiria is such an ethnic melting pot, and there is everything there. Mosques, churches, yurts — everything is nearby.” And this is not just scenery, but a background that influences the characters’ worldview.

“Everything I write, I write for everyone,” Gyulnaz said. Lezhneva deliberately avoids narrow locality, striving to make her texts accessible to everyone. This approach echoes world literature. She cited Astrid Lindgren as an example: “We read her and understand everything perfectly. I wanted the same.”

When the past whispers, and evil spirits wait around the corner

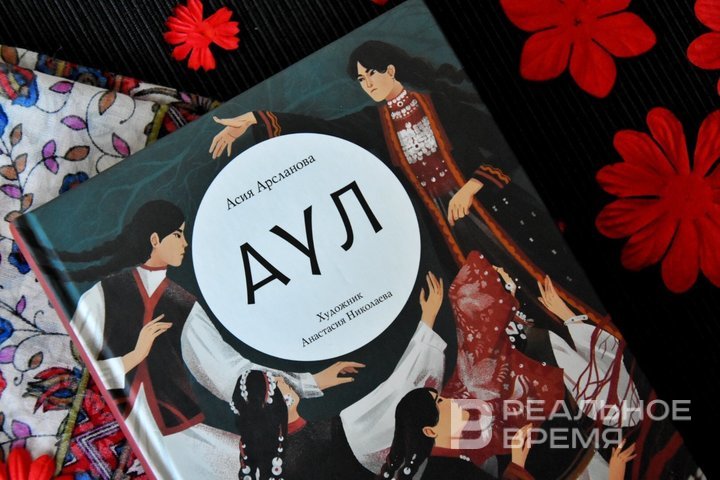

Sashka lost his father and found himself alone in a foreign land. His new life in a Bashkir village became a test and a discovery: unfamiliar customs, fairy tales, songs and a forest full of secrets. What lies beyond the outskirts? What fears lie in wait for the hero, and who are the real monsters? Asiya Arslanova’s book Aul turns a local story into a gripping fantasy in which reality and myths are inseparable.

“When I wrote Aul, I wanted to create something that would be understood and accepted both in Bashkiria and beyond,” the writer said. Asiya Arslanova focuses on the perception of the text by readers: “People who know Bashkir or Tatar read it easier. But for everyone else, this did not become a barrier either — the semantic nuances are clear to everyone.” This balance between the local and the universal led to success. The book was born from the idea of ethnic horror — a plot that draws inspiration from myths and epics. But Aul is not only fantasy, it is a multi-layered text. “We have a strong tradition of epos. Some of them intersect with Turkic ones, some are unique,” Asiya noted. However, she consciously built the story on a literary basis. “I was inspired by Zaynab Biisheva’s novel The Humiliated, Arslanova added.

The characters in Aul are like a bridge between archetypes and cultural specificity. Altynay, a beauty, faces a test familiar from folklore: the bride is taken away to her monstrous groom. “Her dream turns into a dark side,” Arslanova explained. The huntress Shaura is afraid of her own strength and becomes a victim of an attack when she is defenceless. Each character goes through a path that hides personal fears and internal contradictions. The writer did not ignore the topic of education. At the centre is the family of a mullah. “Until a certain point, the only path to knowledge was through religion,” Arslanova said. However, she added an unexpected detail: “The father of one of the heroines, being a mullah, does not actually believe in God. It is a compromise: if you want to be a teacher, become a mullah. The modern intelligentsia also has to find a balance between ideals and reality.”

The Urman forest in Aul is not just a setting. It is a character. “Shurale, spirits, artaki — this entire world was built on the basis of Bashkir folklore,” said the author. Her goal is to show the region's wealth through a fascinating plot. “We know a lot about our culture, but it is important to package it in a way that will interest others,” Arslanova emphasised. The Bashkir epic remains a source of ideas. “If you miss good fantasy, read Ural Batyr. There, girls turn into swans, guys ride lions,” the writer recommended. “We have not yet exhausted the depths. These plots await new interpretations.” Bashkir literature has always been closely associated with women's voices. “We have had female writers since the beginning of the 20th century — Zaynab Biisheva, Khadiya Davletshina," recalled Asiya Arslanova. This heritage inspires modern authors, but they strive for innovation. “We must reassemble traditions, mix them, to show the wealth of the regions in a new way.”

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel and founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.