“Comrades in the lyre”: Agnia Barto

On the 125th anniversary of the poetess's birth: how and what Agnia Barto learned from Mayakovsky, Chukovsky, and Marshak

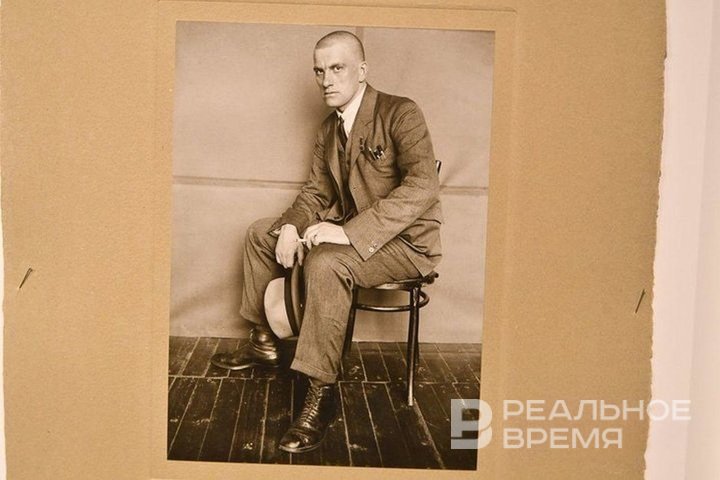

Today marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of Agnia Barto — a poetess whose “Toys," “Bear," and “Bull” became part of the childhood of several generations. Agnia Lvovna Barto (1906—1981) is the author of dozens of books for preschoolers and younger schoolchildren, as well as film scripts. Her poems — simple in form but precise in intonation — are distinguished by kindness, humor, and a subtle understanding of children's psychology. But behind this seeming simplicity lies a great education. Barto had her own teachers and guiding lights. Vladimir Mayakovsky became for her a poet she did not know personally, but whose rhythms and boldness determined the direction of her growth. She was connected to Korney Chukovsky by friendship and many years of professional dialogue. And her relationship with Samuil Marshak was difficult. How exactly Mayakovsky steered Barto towards children's themes, what Chukovsky taught her, and why Marshak called himself like a strict judge — in this report by Yekaterina Petrova, literary critic for the online newspaper “Realnoe Vremya.”

“A pivotal evening”

In her memoirs “Notes of a Children's Poet," Agnia Barto calls her encounter with the poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky a “pivotal evening.” From that evening, she retained “material evidence: a homemade album, filled cover to cover with poems.” In the album, “mischievous epigrams on teachers and girlfriends” coexisted with “numerous grey-eyed kings and princes (a helpless imitation of Akhmatova), knights, young pages that rhymed with 'ladies'.”

The turning point came after someone left a book of Mayakovsky's poetry at Barto's house. Barto recalled that she “read them in one gulp, everything in a row," and then took a pencil and quickly wrote down:

Be born,

New man,

So that the rot of the earth

Dies out!

I bow to you,

Century,

For giving us

Vladimir.

Barto noted that the lines were “weak, naive," but written inevitably. The novelty of Mayakovsky's poems, their rhythmic boldness and rhymes, shook her. “From that evening onward, the ladder of my growth began. It was quite steep and uneven for me," Barto wrote in “Notes of a Children's Poet.” In the album, this is literally visible: if you flip it from back to front, neat quatrains give way to lines arranged in a “ladder.”

Agnia Barto saw the living Mayakovsky later, at a dacha in Pushkino. He lived on Akulova Gora, at the very dacha where “An Extraordinary Adventure Which Happened to Vladimir Mayakovsky in the Summer at the Dacha” was written. Barto recalled how, while playing tennis, she “froze with her racket raised” upon seeing him behind a long fence. She didn't dare approach, although she had prepared a phrase about the “wings of poetry” in advance, and added that, fortunately, she did not utter this “terrible tirade.”

A few years later, the editor of her books, poet Nathan Vengrov, noticed a student-like dependence on “Mayakovskian” rhythms and said: “You're trying to follow Mayakovsky? But you're only following his individual poetic devices... Then decide — try taking on a big theme.” Thus the book “Little Brothers” appeared. Barto admitted that the theme of the brotherhood of workers and their children turned out to be too significant for her and was implemented imperfectly, but the success with children showed that with them, “you can talk not only about small things.”

Of particular importance for Barto was the meeting with Mayakovsky at the first children's book holiday — “Book Name Day” in Moscow. Among the “adult” poets, only he came. In the car on the way to Sokolniki, Barto didn't dare speak to the poet, although she was tormented by doubts — wasn't it time to write for adults? On the platform in front of the stage, she saw only his back and his gestures, but she also saw the children's reaction. After the performance, Mayakovsky said to the young poetesses, among whom was Barto:

This is the audience! You must write for them!

Agnia Barto noted: “His words decided a lot for me.” Soon she learned that Mayakovsky was writing new poems for children. There were fourteen in total, and, in her words, he remained true to his poetics and genre diversity in them.

Later, when she came to the letters department of “Pionerskaya Pravda” to read children's letters and capture the living intonations of the kids, Barto heard from the editor: “You're not the first to think of this. Back in 1930, Vladimir Mayakovsky came to us to read children's letters.”

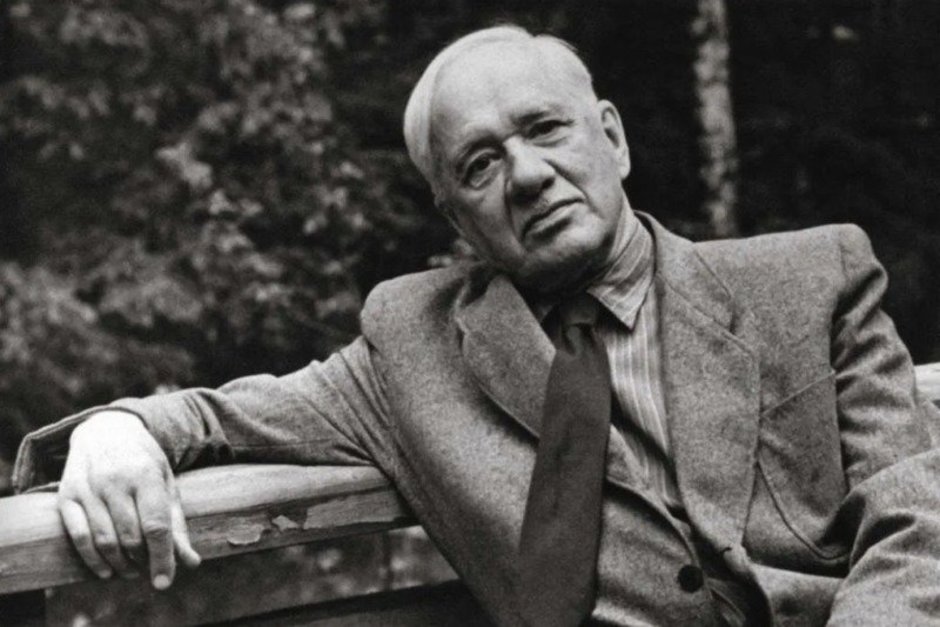

“Unrhymed poems are like a naked woman”

“Many taught me to write poetry for children, each in their own way," the writer said. Among them was Korney Chukovsky. His lessons concerned primarily the nature of verse. Listening to Barto's new poem, Chukovsky “smiles, nods benevolently, praises the rhymes," but immediately adds: “I would be very interested to hear your unrhymed poems.” Barto was perplexed: he praises the rhyme, but suggests writing without it. In a New Year's letter from Leningrad, Chukovsky developed the idea:

The whole strength of such poems lies in lyrical movement, in the internal moves, and that's how a poet is known. Unrhymed poems are like a naked woman. In the clothing of rhymes, it's easy to be beautiful, but try to dazzle with beauty without any frills, flounces, bras, and other auxiliary means.

Barto recalled not understanding him, especially since in his “Commandments for Children's Writers” he asserted: “The words that serve as rhymes in children's poems must be the main carriers of the meaning of the entire phrase.” Gradually she realized it was about lyricism. Barto shared his assessments of her early poems: “it sounds funny, but somewhat shallow," “your rhymes are your own, although magnificent ones alternate with monstrous ones," “here you have a kind of pop wit, my dear... only lyricism turns wit into humor.”

The story with the poem “Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy!” became a separate lesson for Agnia Barto. In May 1934, on a commuter train, she read Chukovsky her lines, attributing them to a five-year-old boy:

Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy!

How I was afraid of spring!

How I was afraid of spring!

I was afraid of spring in vain!

Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy!

You are saved all the same!

Soon, an article by Chukovsky appeared in “Literaturnaya Gazeta” titled “Chelyuskintsy-Dorogintsy!”, in which he wrote:

“I am far from delighted by those pompous, verbose, and flabby poems I've happened to read on the occasion of the rescue of the Chelyuskintsy... Meanwhile, we have in the USSR an inspired poet who dedicated a fervent and ringing song to the same theme, gushing straight from the heart. The poet is five and a half years old... It turns out a five-year-old child worried about these 'Dorogintsy' no less than we did... That's why his lines repeat so loudly and stubbornly, 'How I was afraid of spring!' And with what economy of expressive means he conveyed this deep personal, yet simultaneously nationwide, anxiety for his 'Dorogintsy'! A talented lyricist boldly breaks his entire stanza in half, immediately shifting it from minor to major... Even the structure of the stanza is so refined and so original...”

Barto didn't dare reveal the truth and say she had written those lines herself. The story had a sequel: the lines were played on the radio, appeared on posters, in a variety show revue. At the First Congress of Writers, Samuil Marshak quoted them. Later, several years afterward, Chukovsky did let his young colleague understand that he had guessed about the “fabrication” immediately, but continued to play along as an instructive lesson.

Chukovsky demanded formal rigor from Barto. Coming to visit her, he took a volume of Vasily Zhukovsky from the shelf and read “Lenora," after which he said: “You should try writing a ballad.” Thus “The Forest Outpost” appeared. In the article “A Productive Year” (“Vechernyaya Moskva”), he wrote:

It seemed to me that she wouldn't be able to master the laconic, muscular, and winged word necessary for ballad heroics. And with joyful surprise, I recently heard at the Moscow House of Pioneers her ballad “The Forest Outpost”… A strict, artistic, well-constructed verse, fully corresponding to the grand subject. There are occasional lapses here and there (which the author can easily eliminate), but overall — it's a victory!...

He paid close attention to rhymes, even unsuccessful ones, insisted on precision, and disliked assonances, although he encouraged wordplay. On his advice, Agnia Barto turned to folklore. It was Chukovsky, in her words, who “infected me with his love for oral folk art.” He also supported her satire. About the book “Grandfather's Granddaughter," he wrote:

I read “Grandfather's Granddaughter” aloud and not just once. This is a genuine “Shchedrin for children”... “The Little Brother” is a smiling, poetic, sweet little book…

In another letter, he noted:

Your satires are written from the children's perspective, and you talk to your Yegors, Katyas, Lyubochkas not as a pedagogue and moralist, but as a comrade stung by their bad behavior. You artistically transform yourself into them and so vividly reproduce their voices, their intonations, gestures, the very manner of thinking, that they all feel you are their classmate…

Their last meeting was on June 14, 1969, in Peredelkino. Chukovsky was lying on the balcony after an injection, asking Barto about her “radio searches," talking about the work in 1942 in Tashkent on the “registration and recording of evacuated children," which he conducted together with Yekaterina Pavlovna Peshkova. He asked to hear some cheerful poems. Barto read “He Was All Alone” (a poem about a puppy looking for its owner). After listening, Korney Ivanovich, sensing from the mood of the poem that not everything was smooth in Barto's life at the time of writing those lines, asked: “Did something happen to you... Or to your loved ones?” — and added: “You added the ending later.”

After this meeting, they never saw each other again. Later, Barto received from Chukovsky a promised clipping from a Tashkent newspaper about the work of locating evacuated children — material for her radio program. This was already after his death.

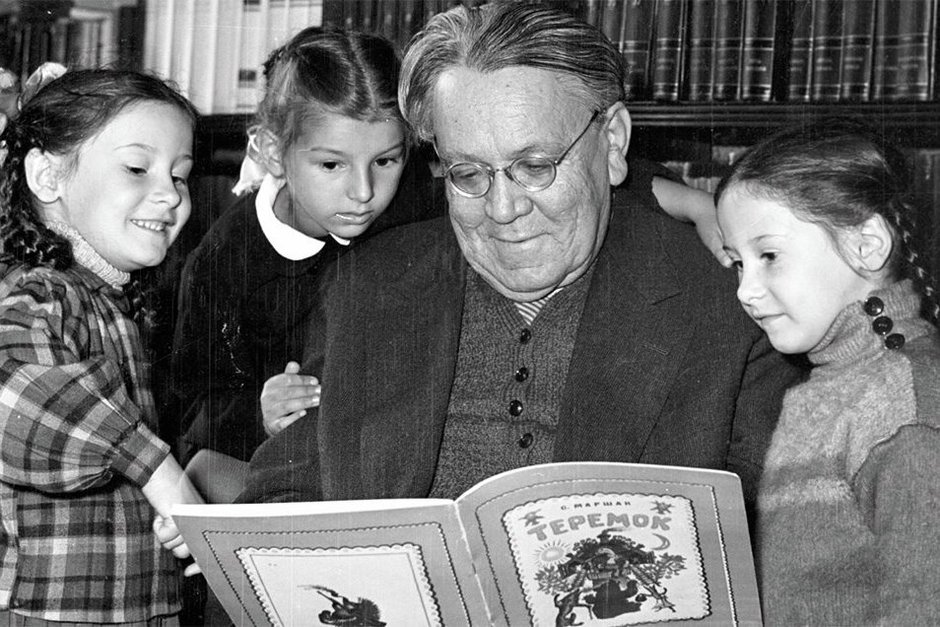

Marshak and the “Sub-Marshakists”

Agnia Barto wrote about her relationship with Samuil Marshak in “Notes of a Children's Poet”: “Our relationship developed far from simply and not immediately.” The context was complex. The late 1920s — early 1930s, VOAPP, RAPP, the division of literature into “proletarian” and “fellow traveler.” In 1925, an article appeared in the magazine “Na Postu," where a “young, beginning writer” was contrasted with Marshak. Barto emphasized: her first book hadn't even been published yet, while Marshak was already a recognized author. The article caused the writer “so many unpleasant experiences” that the consequences were felt for five or six years. Marshak had a negative attitude towards her first books, “I would even say — intolerant.”

When they met at the publishing house, he called one of her poems weak. In response, she repeated someone else's formula:

You can't like it; you're a right-wing fellow traveler!

According to Barto, “Marshak clutched his heart.” Later, disagreeing with his corrections, she said:

There is Marshak and the sub-Marshakists. I can't become Marshak, and I don't want to be a sub-Marshakist!

“Probably, it cost Samuil Yakovlevich considerable effort to remain calm," the writer assessed her own words years later. For these remarks, she later asked forgiveness. But conversations were still “carried out on a razor's edge.” Meanwhile, Barto continued to read and reread Marshak. To the question “What did I learn from him?” she answered concretely: completeness of thought, integrity of the poem, careful selection of words, “and most importantly — a high, exacting view of poetry.”

He praised rarely. “He'd praise two or three lines, and that's it! I almost always left him upset," the poetess recalled. Once she said she wouldn't waste his time anymore. And if Marshak ever appreciated not just individual lines, but a whole poem, she'd be glad to know about it. After a long time, Marshak came to her without warning and said right in the hallway:

“The Bullfinch” is a wonderful poem, but one word needs changing: “It was dry, but I dutifully put on my galoshes.” The word “dutifully” is out of place here.

In the “Uzkoye” sanatorium, where Samuil Marshak and Korney Chukovsky were staying at the same time, an episode occurred that Barto cites as an example of his inventiveness. Samuil Yakovlevich told a young cleaner that the writers had part-time jobs at the zoo: “Marshak puts on a tiger skin, and Chukovsky ('the tall one from room 10') dresses up as a giraffe. They get paid pretty well: one gets three hundred rubles, the other two hundred and fifty," the cleaner recounted her dialogue with Marshak. When Barto told this to Chukovsky, he said after laughing:

That's how it is all my life: him three hundred, me two hundred and fifty…

At Marshak's home, writers, artists, editors, and people of other professions gathered. “Here sounded the poems of Russian classics, Soviet poets, and all those whom, in Chukovsky's words, Marshak 'by the power of his talent converted to Soviet citizenship' — Shakespeare, Blake, Burns, Kipling...” Barto recorded. She recalled that at first she naively considered his children's poems “too simple in form," and even told an editor: “I could write such simple poems every day!” The editor replied: “I implore you, write them at least every other day.”

According to Barto, Marshak was not “kind and fluffy.” She played on his severity in a humorous poem “Almost After Burns," which includes the lines: “When your line is bad, / Poet, fear Marshak, / If you don't fear God…"

“I resemble that, I resemble that, I don't deny it," Samuil Yakovlevich laughed.

A special role was played by the episode with the textbook “Native Speech.” There weren't enough poems about summer. Barto offered her poem. Marshak took the first two stanzas and made edits. He wrote the third stanza himself. The question of signature arose. Marshak asked:

“How should we sign the poem? Two names under twelve lines — isn't that too cumbersome?”

Barto suggested signing it with the pseudonym M. Smirnov. “Thus two real authors became an unreal personality, M. Smirnov," Barto noted in “Notes of a Children's Poet.”

Among the inscriptions in books gifted to her, she especially treasures one: “One hundred Shakespearean sonnets / And fifty-four / I give to Agnia Barto — / My comrade in the lyre.” Barto called this episode the occasion when she and Marshak “truly turned out to be comrades in the lyre.”

Yekaterina Petrova is a literary critic for the online newspaper “Realnoe Vremya” and the host of the Telegram channel “Buns with Poppy.”