From pre-revolutionary angels to Chinese balls and back

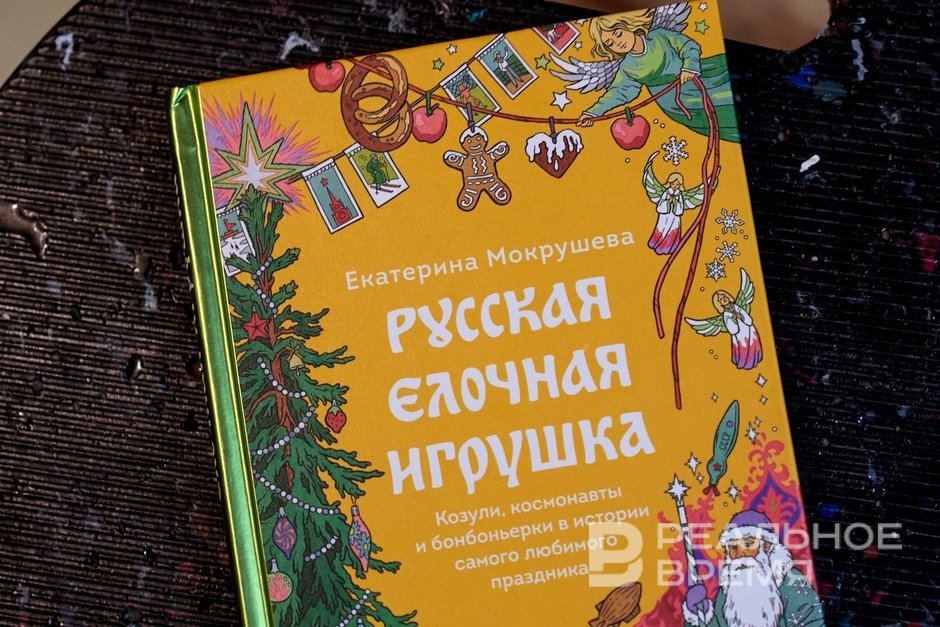

The book of the week is Ekaterina Mokrushova's study «Russian Christmas Tree Toys»

What is hanging on your Christmas tree? Or rather, why did you choose these particular toys? In her book «Russian Christmas Tree Toys», researcher Ekaterina Mokrushova traces the transformation of Christmas tree decorations from the first Christmas trees in the Russian Empire to the present day. She shows that despite their small role in history, Christmas tree toys accurately reflect their time.

A cracker and a bonbonniere for everyone

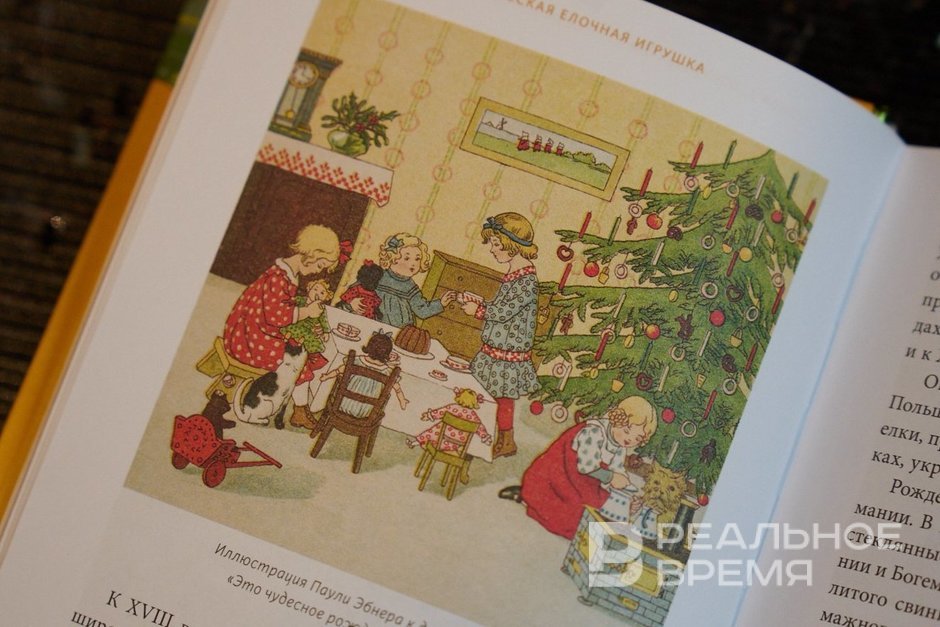

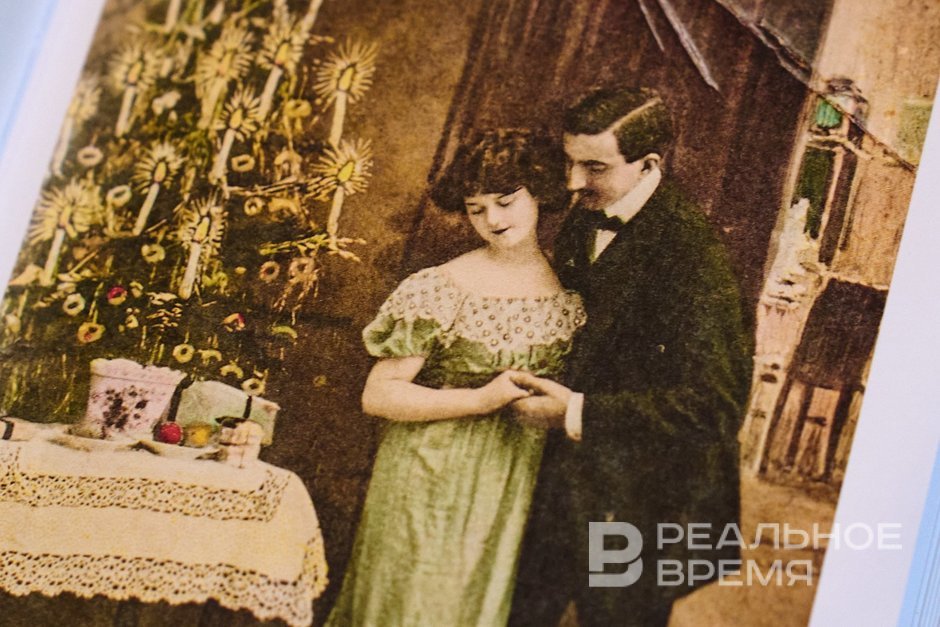

The Christmas tree in pre-revolutionary Russia entered everyday life gradually and at first was a sign of wealthy homes. As Ekaterina Mokrushova writes in her book «Russian Christmas Tree Toys», the main information about early Christmas trees and decorations «has been preserved in diaries, letters and memoirs», and it is through them that we can see how by the 1840s the Christmas tree had ceased to be a rarity in aristocratic and wealthy families. The decorations at first were simple and largely homemade: ribbons, foil, tinsel, nuts painted with gold paint, sweets, candles, paper and fabric toys. This set was repeated in sources for decades and formed a stable visual canon of the pre-revolutionary Christmas tree.

Sweets played a special role. Mokrushova documents in detail that pastila, gingerbread and candies hung on the branches, and the pastila was not white, but brownish — made from baked apple puree. This is confirmed by literary and diary evidence: Saltykov-Shchedrin in 1863 describes a Christmas tree whose branches «bend under the burden of pastila and other sweets», and merchant Ivan Iyudin in his diary in 1862 lists nuts, mirrors and candies as a familiar decoration. According to Mokrushova, such descriptions are important because they show the Christmas tree not as an abstract symbol, but as an object of everyday experience.

Paper decorations — stars, chains, simple figures — were one of the most common elements. Ekaterina Mokrushova notes that shiny paper stars were regularly mentioned in records, as were «paired confectioneries», which I. P. Yuvachev wrote about in 1890. Even in poor urban families, the Christmas tree retained this set: in E. A. Beketova's story, the Christmas tree is decorated with gilded nuts, apples, candies and wax candles. According to the researcher, it is such descriptions that allow us to talk about the social breadth of the custom by the end of the 19th century.

At the turn of the century, the Christmas tree became not only a domestic, but also a commercial phenomenon. Mokrushova thoroughly analyzes catalogues and price lists: stores and festive bazaars sold both individual toys and ready-made sets. The winter price list of the trading house «I. N. Purishev and Son» for 1901 included crackers, cardboard toys, nuts, candles, glass balls and beads, and the «I. Glazunov's Christmas Bazaar» catalogue of 1914 offered entire «collections» for public Christmas trees. The author emphasizes that such sets were designed for mass use — «so that every child would receive a cracker and a bonbonniere».

A special place was occupied by cardboard toys — relief toys made of thin cardboard. According to Ekaterina Mokrushova, they became fashionable in the 1870s and became the most common factory-made decorations before the revolution. They were valued for their affordability and variety: stars, carriages, helmets, baskets and boxes were made from stamped cardboard. The Moscow factory of A. Glenk offered products not only from cardboard, but also from satin, silk, velvet and gelatin, including semi-transparent boxes and lanterns in 1901. The author extracted this information from trade catalogues.

Alongside the purchase of decorations, the tradition of homemade crafting persisted. The researcher emphasizes that homemade bonbonnieres, chains and cardboard toys were valued not only for their low cost, but also as part of a family ritual. The memories of A. N. Tolstoy, T. L. Sukhotina-Tolstaya and N. M. Gershenzon-Chegodayeva describe the process in detail: they boiled glue from starch, gilded nuts, glued paper chains and boxes. These testimonies, collected in the book, show that the pre-revolutionary Christmas tree was a combination of purchased novelties and handicrafts, and it existed in this form until 1917.

Rehabilitation of the Christmas tree

After the revolution, the Christmas tree, as an attribute of a religious holiday (at that time, Christmas, not New Year, was celebrated), was erased from public and domestic spaces. But the tradition could not be completely eradicated. The return of the Christmas tree to Soviet life is associated with the publication of Pavel Postyshev's letter in the newspaper Pravda on December 28, 1935. Ekaterina Mokrushova calls this moment a turning point: the Christmas tree was not just allowed, but recommended as a mandatory element of children's New Year. The same issue of the newspaper noted that Christmas tree toys were almost impossible to buy, but two days later, Pravda published a photograph of children near a Christmas tree in the window of Detsky Mir. According to the researcher, the Christmas tree was rehabilitated in an extremely short time and finally lost its religious significance, turning from a Christmas to a New Year, Soviet one.

Immediately after that, the mass organization of New Year's Christmas trees began across the country — in schools, pioneer houses, orphanages. Mokrushova cites documents and newspaper publications showing that the new tradition was introduced centrally and simultaneously. In Sverdlovsk at the end of 1935, a special document of the Central Committee of the Komsomol was published on holding New Year's evenings with the efforts of the students themselves, and in Baku, a city-wide children's carnival was held with costumes of pilots, parachutists and representatives of the peoples of the USSR. The author emphasizes that, unlike the pre-revolutionary practice, the New Year's Christmas tree was «imposed» on everyone at once and became part of the official festive culture.

The new Christmas tree needed new toys, and their themes quickly changed. As Ekaterina Mokrushova writes, if earlier the decorations referred to the Gospel story, now the Christmas tree could «tell the story of the country and the current agenda». In the 1930s, assembly toys made of glass tubes and beads became widespread, and after the dirigible parade of 1935, dirigibles, airplanes and parachutists appeared on the Christmas trees. Instead of the Star of Bethlehem, a red five-pointed star was placed on top, which in the Soviet context had nothing to do with Christmas and was interpreted as a political or cosmic symbol.

Materials and production technologies in the pre-war period remained diverse and largely forced. Mokrushova describes in detail that toys were made of cotton wool, cardboard, glass and even light bulbs with the base cut off. Cotton wool figures — pioneers, skiers, polar explorers, animals — were produced by numerous artels and factories, annually selecting successful samples at competitions. In 1936, mass production of glass toys began, and price lists of the late 1930s included balls with a hammer and sickle, stratostats, bugles and glass fruits. At the same time, there was a shortage, and, as the author notes, homemade and «quasi-toys» not intended for festive decor were often hung on Christmas trees.

Mass industrial product

In the second half of the 20th century, the Soviet Christmas tree toy finally became a mass industrial product. Ekaterina Mokrushova writes that already in the 1950s and 1960s, «the production of Christmas tree toys flourished, experiments were conducted with materials, form and themes», and factories worked to meet stable demand throughout the country. The assortment expanded not only quantitatively: stable visual themes were fixed on the Christmas tree, which passed from year to year and were reproduced in different materials — glass, cotton wool, foil, chenille, later — plastic and polyethylene.

After the war, toys increasingly turned to images of peaceful everyday life. Mokrushova notes the popularity of kettles, samovars, cups and other household items painted by hand, which were perceived as signs of a well-organized life. At the same time, the practice of regular screenings and exhibitions of new samples continued, where children and adults discussed the shapes, themes and convenience of toys. The author emphasizes that such discussions directly influenced further production, shaping the demand for unbreakable and thematically diverse decorations.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the fairy tale theme took hold on the Christmas tree. The release of toys based on Pushkin's fairy tales, according to the researcher, was so successful that «the fairy tale characters pleased the buyers and stayed on the Christmas trees for a long time». This line gradually вытеснила military and ideological images of the pre-war period, although the connection with the current cultural agenda remained. The book emphasizes that fairy tale characters became one of the most stable categories of Soviet Christmas tree toys.

The 1960s brought space to the Christmas tree. Ekaterina Mokrushova describes how, after Gagarin's flight, spires, astronauts, satellites and sets of balls with images of planets appeared. She points out that «the space theme often intertwined with the New Year theme». This was manifested not only in toys, but also in illustrations of children's magazines and New Year's printing. The space theme existed in parallel with the fairy tale theme, without completely displacing it.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the production of Christmas tree decorations became stable and technologically diverse. Factories produced large series of sets, actively used polystyrene, lavsan film, and foam. The author notes that the ideological burden gradually faded into the background: «the themes of the decorations increasingly rarely referred to current events», and balls, icicles, cones and abstract shapes dominated the Christmas tree. The color palette became brighter, especially in the 1980s.

At the same time, even in the late Soviet period, new products continued to appear regularly. Mokrushova cites data on dozens of new types of decorations released in the early 1980s, including sets based on literary plots and experiments with frosted glass. At the same time, the researcher emphasizes that mass production did not negate diversity: the Christmas tree toy remained «one of the most flexible and responsive elements of festive culture», which could adapt to new materials, housing formats and trading practices.

Further and further from the state agenda

The crisis of the 1990s became a turning point not only for the country, but also for the Christmas tree toy. The production of glass decorations formally continued, but, according to Ekaterina Mokrushova, these years «became a time of difficult trials associated with the weakening of the creative development of a sustainable artistic image». The largest manufacturers remained the Klin «Yolochka» and the Moscow «Iney», but the market was flooded with imported plastic toys, primarily from China. The author notes visual shifts: balls with zodiac symbols began to appear on the Christmas tree, the role of fashion, not the state agenda, increased, and «the Christmas tree began to reflect not the history of the country, but the tastes and preferences of adults».

At the same time, in the 1990s, there was a return of Christmas symbols. Mokrushova notes that candles, angels, Christmas greetings reappeared in print and children's magazines, and Christmas was officially included in the holiday calendar. At the same time, the trade in domestic toys remained unstable: stores were more willing to purchase foreign products, and the authorities had to provide administrative support to the factories. The author gives examples showing the similarity of the situation with the early 1930s: the gap between production and trade, outdated equipment, limited assortment with persistent demand.

In the 2000s, a gradual recovery of the industry began. State support allowed factories to increase production, although artists often worked with existing forms. Solid-colored and minimalist Christmas trees came back into fashion, but at the same time, interest in traditional glass toys with hand-painted designs grew. Mokrushova emphasizes that it was during this period that «Soviet toys began to be perceived as a cultural and collectible value», and factories returned old forms, assembly toys, beads and figurines from childhood to their catalogues.

Concluding the book, Mokrushova notes the main feature of the modern Christmas tree toy — diversity. Today, a variety of materials — glass, plastic, cotton wool, wood and textiles, factory and homemade decorations, new forms and restored pre-war technologies — can coexist on one Christmas tree. At the same time, the Christmas tree toy remains not a utilitarian object, but a ritual thing, whose significance is determined not by rules and fashion, but by memory and the repetition of the gesture. The book «Russian Christmas Tree Toys» traces this history consistently — from the first Christmas trees to the present day, relying on documents, press, catalogues and visual sources, and shows the Christmas tree as a rare example of a cultural tradition that has changed but not been interrupted.

Publisher: MIF

Number of pages: 224

Year: 2025

Age rating: 16+

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary reviewer for the online newspaper «Real Time» and the host of the telegram channel «Macaroon Buns».