The city against loneliness: why Richard Sennett is sure that we are doing everything wrong

Architecture doesn't just decorate cities — it trains us. How do concrete jungles shape consciousness, why is chaos better than order, and why do Kazan need “winking” buildings?

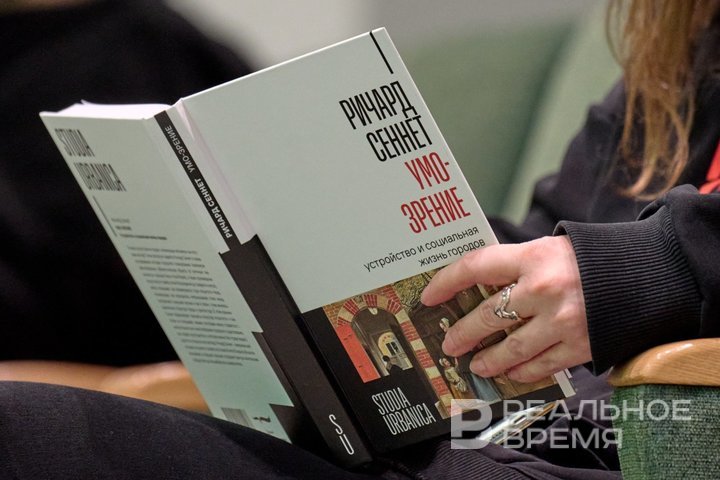

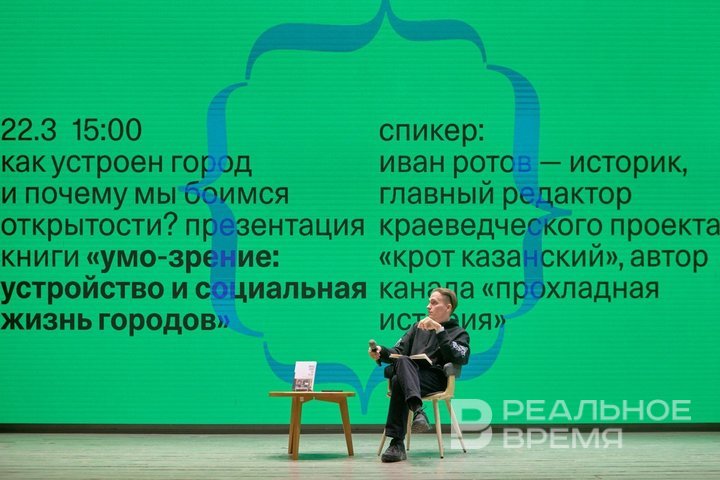

How do we look at the city— and how does it look at us? Richard Sennett's book Mind-vision: the Structure and Social Life of Cities was presented at the market of the New Literary Review in the National Library of the Republic of Tatarstan. Historian and editor-in-chief of the Kazan Mole local history project Ivan Rotov explained why we are used to seeing the city differently than we should and what Sennett offers instead of the usual isolation.

Leave the room

Richard Sennett is a man who has spent his entire life studying how cities are structured and why they shape us the way we are. A sociologist, urbanist, philosopher, he teaches at the London School of Economics, worked at Harvard and MIT, headed the New York Institute for the Humanities and even headed the UN Commission on Urban Development. There is an interesting detail in his biography: he was born and raised in the infamous Chicago social project, Cabrini Green. In the 1960s, this area was synonymous with poverty, crime, and failed urban development. This is perhaps where his interest in the topic of cities comes from — Sennett has seen since childhood how architecture affects people's lives.

In his book, Mind-Seeing: The Design and Social Life of Cities, Richard Sennett argues that cities should not turn us into loners. But that is exactly how they are structured now. “The state wants us to be lonely in a big city, to sit in our apartments,” explained Ivan Rotov. However, Sennett does not believe in a conspiracy of architects who allegedly deliberately make cities uncomfortable. On the contrary, all attempts to reform urban space were based on good intentions. It’s just that they almost always ended in failure. For example, the idea of making train stations, airports and public passages as convenient as possible for movement. At first glance, this is logical: it is easier for passengers to move around, there is less crowding, people do not interfere with each other. But there is a side effect — we stop interacting. The city becomes not a meeting place, but a transit zone, where everyone is on their own. According to Sennett, the very concept of “comfortable” housing, where a person can “grow in spirit” alone, breaking away from the world, is a mistake. “We were wrong when we decided that this is how it works,” Rotov recounted his theses. The city, Sennett believes, should not isolate, but connect.

If you explain the essence of Sennett's theory in a nutshell, you can do it with a line from Brodsky: “Don't leave your room, don't make a mistake.” Sennett says the exact opposite: not leaving your room is a mistake. The sociologist argues that self-knowledge is impossible in isolation. A person is a social being, and only through interaction with others can we understand ourselves. “According to Sennett, you should not only leave your room, but ideally also go to a public bathhouse and look into the sad eyes of a tired man after a steam room. And then we will become closer to each other and understand ourselves better,” Rotov joked. This image is not a random curiosity. In the book, Sennett talks about the importance of public spaces where people collide, exchange glances, emotions, even if fleetingly. Modern cities are designed to have as few such clashes as possible.

Medieval city: labyrinth of fear and temple of order

“Sennett doesn’t like Christianity very much,” Ivan Rotov warned right away. In his opinion, the urbanist sees Christianity as the reason for the destruction of the ancient ideal of urban space. The polis, which was a place of social interaction, turned into a disunited, frightening labyrinth. “Medieval cities, unlike the polis, were very clearly divided into what a professional architect built — primarily the temple — and the chaotic, unpleasant, disorganized, unsafe everything else,” Rotov explained.

A fundamentally new division of space arose in these cities. There were safe zones — the temple, monasteries, areas protected by fortifications. And there were streets that became risky territories: noisy, dirty, overcrowded with merchants and marginalized people. “At that moment, squares — the spaces of the polis where informal communication could be conducted — disappeared from the cities,” Rotov said. It was then that the street began to be perceived as a threat.

“Until 1768, Kazan developed exactly as Sennett describes. We had a fortress — and around it uncontrolled, unsafe, unorganized chaos,” said Rotov. Urban structures were not created according to a plan, but spontaneously. Narrow, crooked streets, the absence of clear boundaries between residential and commercial areas, constant reconstruction — all this made the space difficult to manage and dangerous. People did not feel like masters of the city, they simply coexisted with it, avoiding unnecessary contacts. However, this state did not last long. The 18th century brought a new type of urban development to Kazan, based on strict calculations.

In Europe, they began to use a regular city plan — a strict grid of blocks, division into zones and functional areas. Architects designed space from scratch, without regard for the natural landscape. Sennett harshly criticizes this practice. “This is an arrogant story about how an architect can build a city based on his ideas and not focus on the natural landscape,” Rotov recounted the sociologist's thoughts. A striking example is Manhattan, divided into ideal squares that continue even when a block crosses a river and there are no bridges. “We ignore reality by reproducing the grid,” Rotov said.

The same thing happened in Kazan. “In 1768, they decided to turn the crooked, slanted, terrible Black Lake, cut by ravines and hills, into one neat rectangle,” the historian said. For this, serfs manually carried thousands of pounds of earth, filled in ravines, and levelled the terrain. The result? “All the houses around Black Lake stand on fill soil. That's why our Alexandrovsky Passage collapsed, the Mergasovsky House cannot be restored. This is the urbanism of the 18th-19th centuries — the fight against nature,” the historian added.

But is it possible to build a comfortable city without fighting the natural landscape, but cooperating with it? Sennett thinks so. And there are examples of such successful urbanism in Kazan. “An unobvious, but interesting one is the building of the Unix sports complex,” suggested Rotov. The building is built into the landscape so that the entrance from Nuzhin Street is on the fifth floor, and from Pushkin Street — on the first. This is the very idea that Sennett talks about: we work with nature, and do not try to destroy it. But even this project remained unfinished. “The doors on the first floor are closed, and instead of uniting with the landscape, you just get irritated because you have to go up,” Rotov noted.

Rooms, squares and boundaries: how urban thinking works

Until the 19th century, the idea that each room has its own function was not as obvious as it seems to us today. Houses were multitasking: bedrooms doubled as guest rooms, and sanitary needs were not separated from public life. As Ivan Rotov noted: “Having guests, doing your business, and sleeping in the same room is not a problem. It’s reality.” It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the process of specialization began.

Each space gets its own function: bedrooms are for sleeping, dining rooms are for eating, and offices are for working. In Kazan, an excellent example of this principle is the Lobachevsky House. “Go to the Nikolay Lobachevsky Museum. And there you will see this enfilade, where one room is for dancing, the second room is for receiving and communicating with guests, another room is a library, and so on,” Rotov gave an example. However, despite the rationality of this approach, it did not lead to the expected results. Sennett warned that strict segmentation of space did not improve the quality of life, but, on the contrary, led to social isolation. “An apartment, instead of a spiritual laboratory where we can read and work well, has turned into a system of hidden barriers,” the historian said. This is how women's rooms, parental areas, and children's spaces appeared. The division has intensified, but has not led to openness.

Unlike Zygmunt Bauman, who saw squares as a control tool, Richard Sennett views them as a key element of urban interaction. They can connect areas, form routes, and become points of attraction. However, not every square performs these functions. An example of a failure is Kazan's Millennium Park. “This is an absolutely dead place in social terms, where nothing happens. And most importantly, there is not a single reason to be there,” Rotov said. He compared it to the urban spaces of Rome, where streets lead pedestrians from one point to another, creating a continuous route. Millennium, on the contrary, does not connect important areas of the city and does not motivate movement.

But there are also successful examples. One of them is the historical Yunusovskaya Square at the beginning of the 20th century. It was organized not from above, but by the city residents themselves. “Yunusovskaya Square was divided into four parts. “A garden of love, a garden of sorrow, a garden of dances and a Maidan,” Rotov listed. Young couples met here, servants took a break from work, people danced, and parents discussed business. Sennett would have supported this principle — he believed that successful urban spaces are born in the process of live interaction.

Space, glass and an attempt to comprehend the universe

According to Richard Sennett, modernism was not just an architectural movement, but an attempt to express new ideas about the world that arose in the second half of the 20th century. The connection with the discoveries of physics was obvious: time began to be perceived as a special case of space, and an observer under certain conditions could see much more than before. In practice, modernist architecture is not only minimalism and functionality, but also a special view of transparency. “A glass door simultaneously isolates and invites you in,” Rotov said. It is important not only to see the facade of the building, but also to understand what is inside. This is why modernists actively used glass, created open galleries and through spaces.

In Kazan, this idea was embodied in the Printing House on Bauman and in the same UNICS. “Both of these buildings used to look a little different. They had open galleries, which were later glazed. Now it doesn't work like that,” Rotov noted. Previously, walking along Pushkin Street, you could look into Unix and see its inner life. Now this idea has been erased. But what happens when the idea of open space goes too far? “A glass tower, completely open to the world, is that what we need?” Richard Sennett asked. And then he answered himself: no.

Modern skyscrapers with their mirrored facades isolate a person from the real world. “You sit in a beautiful office, you see the world outside the window, but you are isolated from it, you don't hear it,” Rotov explained. In such buildings, the windows do not open, the ventilation is closed, and going outside is a whole expedition. “It turns out that some 19th-century mansion with an internal garden and small windows is much more open to the world than a completely transparent glass tower,” the historian suggested. This is the paradox of modern architecture. We are promised openness, but in the end, a person ends up locked in a glass box.

Sennett analyzes the failures of architects, noting that the main problems remain unresolved. “People feel frustrated. They are uncomfortable either in their apartment or on the street,” added Ivan Rotov. What does Sennett offer? He records street practices, for example, graffiti on the walls: “Vasya was here.” This is not just hooliganism, but an instinctive desire to leave a mark, to prove one’s presence. “A person cannot change the structure of the city, but he can work with the material. He sees white plaster and writes on it,” said Rotov.

But the main thing that Sennett proposes is the mutation of buildings. The city must change so as not to become a museum exhibit. “We should never cling too much to the preservation of historical buildings, otherwise another conflict will arise — between people and architecture,” Rotov quoted the author. The most striking example of a mutating building in Kazan is the National Library of the Republic of Tatarstan. The building of the Lenin Memorial, then the Kazan Cultural Centre, was too dark in its last years. “Then the idea came up to make a library here. We had to demolish the walls and make glass facades, but this allowed the building to live on,” the historian noted.

And this is Sennett’s key idea: comfort in the city is created not by the absolute preservation of the old, but by its reasonable transformation. If the space stops working, it must be changed. Otherwise, the city becomes lifeless.

The city as a living organism

“I really want and it is very important that there is a dialogue between the buildings, so that the buildings literally throw some statements at each other,” Ivan Rotov noted. Sennett says that the city consists of heterogeneous buildings: scientific centres, residential complexes, recreation areas. There are no more integral, predetermined projects. But it is important that they interact. An example is the Guggenheim Museum in New York. A super inappropriate building. “Amid pseudo-Gothic, low buildings — and here a concrete spiral falls from the sky,” Ivan Rotov commented on Sennett's example. But it is this contrast that makes the space come alive. The inconvenient, cramped plot of land did not become a limitation, but, on the contrary, emphasized the uniqueness of the building.

In Kazan, such a dialogue can be seen on Kasatkina Street. “Walk past the specific residential complexes, past the neo-Gothic tower. It has an openwork lattice in the Arabic style on the side. And a little further — a building from the 1980s, a government building, Soviet national romanticism. There is also a lattice with a national ornament. This may be an accident, but it may also be a thoughtful winking of buildings,” Rotov advised. Sennett likes this: the city is not a frozen monument, but a constant exchange of remarks.

Sennett writes that deconstructivism is another unsuccessful project to save us from frustrations. Architecture without straight lines knocks a person out of their usual state. “The classic city of the new era puts you to sleep. You just walk through it. And the monuments of deconstructivism are made to slap you, to shake you up,” Ivan Rotov noted. In Kazan, such an example is Crystal residential complex on the bank of the Kazanka River — uneven lines, out-of-place geometry. Or another version: the TAIF business centre. “Go around it, there is literally a street with a passageway from above inside the building. If you stand in the centre of this frame, you will see a clear rectangle of sky, modern buildings of Kazan, and a lot of technological buildings around. Historical Kazan and the Fuchs Garden disappear,” Rotov suggested. The city in this place creates a special effect: you stop feeling where you are and start thinking.

“The city should be our common place for creativity and change,” Rotov emphasized, retelling Sennett’s ideas. But this is a dangerous idea: does it mean that we should constantly rebuild monuments and demolish old buildings? “Sennett is very careful in his approach to this idea, but his final conclusion is precisely this: we do not need an open-air museum. We need a space that changes,” the historian added. These changes are already happening. For example, apartments. Modern expensive housing increasingly looks like a single space: a bed, a bath, a kitchen and a living room without partitions. This is a return to ancient traditions — ancient atria, Scandinavian longhouses. People are not looking for isolation, but an open structure where interaction is inevitable.

“That is why Sennett’s book is worth reading. It gives a view of a city that is not static. It is a city that talks, argues and changes. And this is its strength,” Rotov concluded.

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel and founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.