Celebrations without borders: How New Year celebrated by different ethnic groups in Russia

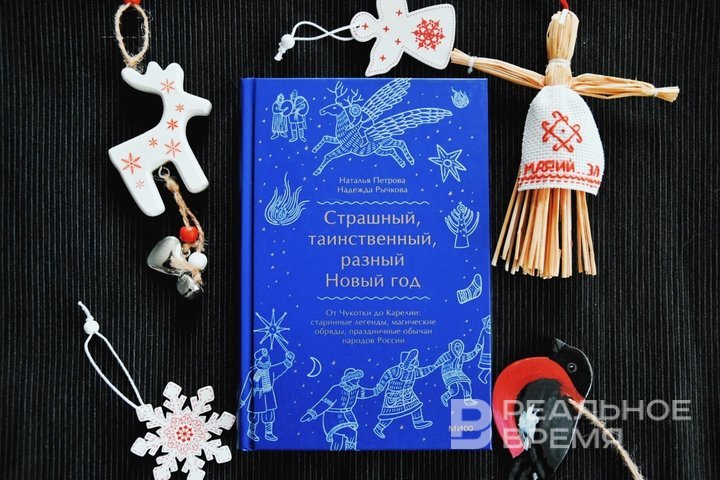

Secrets of National Customs, Surprising Traditions, and the Magic of the New Year’s Transition in the Book “Terrifying, Mysterious, and Diverse New Year”

Russia is a country where the New Year is celebrated eleven times according to time zones. But this is just the beginning.: New Year's Eve is celebrated here not only at different hours, but also on different days, months, and sometimes even in different seasons. The traditions are so diverse that the spirit of the holiday sounds completely different — from winter frosty feasts to summer rituals in honour of nature. Natalia Petrova and Nadezhda Rychkova wrote about all this diversity in the book “Terrifying, Mysterious, and Diverse New Year”

The diversity of times and peoples

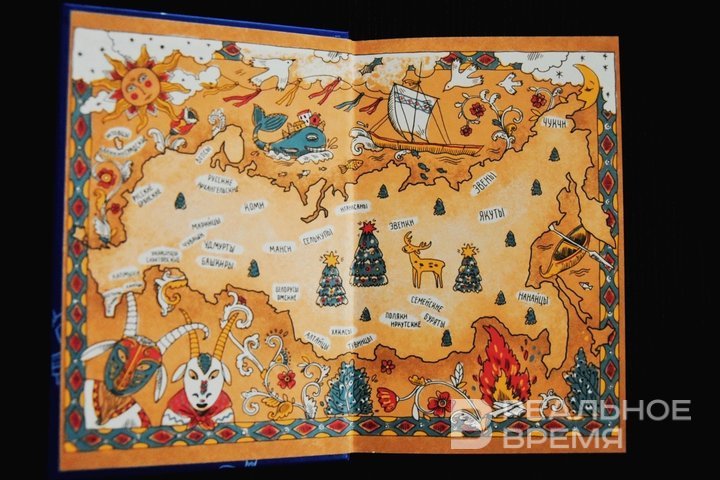

In a country with more than 180 peoples, the usual dates and formats of the New Year look like only part of the general kaleidoscope. As the authors of the book note:

In Russia, there is a tradition to celebrate the New Year eleven times: starting with Chukotka and ending with Kaliningrad. We decided to show that the New Year can be celebrated many more times and not only on December 31.

The holiday can take place in spring, summer, autumn and winter. Farmers, for example, traditionally celebrated the New Year in early spring, marking the start of agricultural work, while herders observed it during the livestock birthing season, most often in summer. Hunters and fishermen had their own landmarks. Among the Yakuts, there was a month called “feeding the foals," among the Evenks, a period known as “greening of the larches," and among the Selkups, the “month when they dry fish.” The year of these peoples began when nature pointed to another important milestone. At the core of these traditions lies the common meaning: the transition from the old to the new. This time was considered particularly important, but also dangerous.

According to traditional beliefs, the boundaries between the human and non-human worlds are violated during this period.

This moment explains such familiar rituals as mummification or fortune-telling. Wearing costumes of non-human creatures, people seemed to protect themselves from them, turning the game into a magical action. The concept of “New Year” as a uniform beginning of a cycle is linked to the spread of world religions. Before that, many nations did not have it, and life was divided into “winter” and “summer” periods.

Despite the differences in time and rituals, all peoples have universal symbols and practices.

- Protection from evil forces. Amulets were used, prohibitions were observed.

- Getting rid of the old. Fire and water helped to put all the bad things in the past.

- The magic of the new. Festive feasts, wishes, and even little things like new clothes — all this provided a symbolic transition to the better.

“As you celebrate the New Year, so you will spend it” — a familiar proverb is rooted in the traditional worldviews of the peoples of Russia. This simple, at first glance, thought carries a deep meaning. Generous food, dancing, songs — all this is a way to appease the forces of nature, strengthen the connection with the world of spirits and ancestors, ensuring well-being for the whole year.

How the Yakuts celebrate the New Year: ancient rituals and dancing under the sun

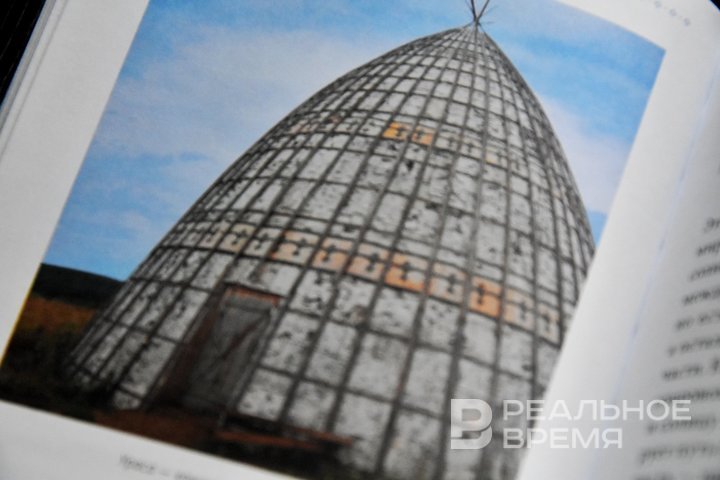

The Yakut New Year is not a winter holiday with Christmas trees and tangerines, but a summer ceremony associated with the cult of the sun. Its roots go back to ancient times, when nature, animals and the rhythm of the seasons were the basis of life. You open your eyes and in front of you there is a huge green meadow decorated with felled birch trees. Every birch tree is wrapped with a ribbon — salam — intertwining with white horsehair. For the Yakuts, this is not just an ornament, but a protection: the demons of the abasa cannot penetrate such a fence.

In the center of the glade, symbolic gates are built from two wooden posts with a crossbeam. Previously, a vessel filled with kumis was hung on it, but now, near the gates, they place festive “chorons” — beautifully carved wooden vessels adorned with bundles of horsehair. These vessels are sacred objects. They connect a person with the gods. To the northeast of the gates, a “serge” is set up — a hitching post for the heavenly horses, which, according to Yakut beliefs, are sent by the deities for the celebration. And in the centre of the clearing there stands Aal luk mas, the mythical tree of life. The upper branches of the tree symbolise the world of the gods, the middle branches symbolise the world of humans, and the roots symbolise the underworld of spirits.

The history of the holiday is connected with the legendary Elle, one of the ancestors of the Yakuts. They say he built his farm in the Tuimaada valley, made vessels for kumis, and for the first time invited his family to a holiday. On that first Ysyyah, Elley made an offering to the supreme deity Yuryung Ayyy Toyon, and since then this ceremony became annual. The celebration begins around a campfire in a traditional dwelling, Mogol Uras. Here, an honorary old man or steward reads prayers addressed to the gods. Next to it, there are chorons filled with kumis. Sip by sip, the drink is passed from one person to another. Each vessel opens the well-being for the family.

Kumis, like other dishes, has a special meaning in Ysyakh. They prepare salamat porridge made from flour with butter, black pudding from mare intestines, and baked horse meat. Food embodies abundance, and its taste is a true metaphor for Yakut life.

The highlight of the celebration is the osuokhai circular dance. People hold hands and move around Aal luk mas in the course of the sun. The singer begins the song, the others pick up her refrain. The dance is divided into three parts: bowing to the sun, slow steps symbolising the path to the gods, and, finally, jumping. Jumping is the culmination of the dance. They symbolise the ascent to the world of deities. In 2012, the Yakut osuokhai became a record: more than 15 thousand people united in a common circle.

Another tradition of Ysyakh is the struggle between the spirits of the old and new year. Two young men are dressed in the skins of foals: a white one — a symbol of the new year, and a black one — the outgoing one. In a fight, white always wins. Victory is a sign of renewal and hope. At the end of the celebration, the master of ceremonies throws up a sacrificial spoon. If it falls upside down, the year will be full. To drive away old problems, they throw an old hearth hook into the fire. It is forbidden to drink kumis to the bottom on Issyakh — drops of the drink must remain in order to preserve the inexhaustibility of life. If someone gets angry during the holiday, they will have an angry year. But if you eat enough, you can count on abundance.

Crow's wedding and the “miracle swing”: how Bashkirs celebrate the New Year

The Bashkir New Year, known as Kargatuy or The Crow Festival, marks not only the arrival of spring but also embodies centuries-old traditions rooted in respect for nature and its cycles. The holiday begins even before the official day of the celebration: children go from house to house, croak and invite everyone to the crow wedding. For Bashkirs, the crow is a sacred symbol. According to a local legend, crows descended from Adam. However, due to laziness, they lost their human appearance. Echoes of this myth have been preserved in respect for birds and even in rituals.

Porridge, which will be the main treat of the holiday, is prepared from products collected by the entire community. Women dressed in bright costumes decorate themselves with coins and shells. They are the main characters of the holiday, because they are the ones entrusted with conveying their fertility power to nature. Porridge is cooked outside, stirring thoroughly so that it does not burn. This process is a real performance. When the dish is ready, it is served at a communal table, spreading a tablecloth under decorated trees. There are no traditional chairs here — everyone sits on felt. In addition to porridge, there is cottage cheese, bread, and butter on the table so that everyone can make a treat to their taste.

However, porridge is not just for people. It is laid out for birds, especially for rooks and crows, to attract their attention and gain the favor of nature. “The more plentiful the food for the birds, the more prosperous the year will be," says the legend.

One of the striking rituals of Kargatui is the decoration of trees. The branches are covered not only with ribbons, but also with silk shawls, coins, and beads. It is believed that this helps trees to bloom faster and gain strength. Dances are performed next to decorated trees, imitating the movements of birds' wings.

After the meal, the fun begins. One of my favourite pastimes is playing “crow porridge.” One girl walks around with porridge in her hands, while others surround her, cawing like birds. There are other contests: tug of war, jumping over a pit, running with an egg in a spoon. A special place is occupied by traditional swings. They are made huge — up to 10 metres high.

Northern riddles of the New Year: goats, fortune-telling and hooligans

In the Russian North, New Year is not just a date. This is a whole winter cycle of holidays, full of rituals, omens and rituals, many of which have been preserved since ancient times. The climax of this period is the Holy Nights — a time when faith, imagination, and playful mischief blend together. It is customary to start winter celebrations with the preparation of goats, unique northern gingerbread. These figures made of rye dough depict deer, horses or cows. They are made from dark dough mixed with burnt sugar, and decorated with white details. The famous northern storyteller Stepan Pisakhov described the goats in this way:

Kholmogorsky goats resemble deer. There are apples on the horns, and birds on the apples. The size of such a kuzuli can be 5 to 6 vershoks. They are also molded in small size — about a vershok.

These kozuli are not only eaten but also given as gifts: to revelers, children, and neighbours. The remaining of kozuls go to pets — they also need to be gifted so that the year is successful.

During the Holy Nights, dressing up is an important part of the fun. In the first week, it is customary to dress up “beautifully” — to wear vintage sundresses and shawls. But during the “scary evenings," the participants' imagination runs wild: turning coats inside out, soot on faces, and underwear worn over clothes. Disguised people sing carols, wish prosperity to the hosts, and sometimes leave traces of their visit. For example, they bring snow into the house or leave the gate wide open.

Holy Nights is the best time for fortune-telling. One of the ancient ways is to go to a stand and draw a circle with a candle. Sitting inside, listen to the sounds in silence: the ringing of bells promises a wedding, music — joy. Brave girls can put a cockroach under their pillow, asking the insect to show their future spouse in a dream. Another popular ritual is to get a stone out of the hole. Light one predicts good luck, dark one predicts difficulties.

Holy Nights are incomplete without mythical characters. Shulikuns are water demons that are believed to come ashore on Christmas Eve. They scare travelers, and sometimes even give yarn as a gift, leaving it on a stick stuck in the snow. To save the house from their visit, they draw crosses with chalk or draw them in the air with a knife. On Christmas Eve, young people make evening parties where girls demonstrate their skills in spinning, and boys hide spinning wheels, expressing sympathy.

The book notes that there is no single “Russian” or any other New Year's tradition. Even in neighboring regions, customs can vary greatly. But this does not prevent us from finding similarities and common patterns. Each chapter of the book “Terrifying, Mysterious, and Diverse New Year” reveals not only the uniqueness, but also the deep relationship of customs with the way of life, nature and history. These holidays teach you to cherish traditions and perceive the New Year as something more than just a date on the calendar.

Publisher: MIF

Number of pages: 256

Year: 2023

Age limit: 16+

Ekaterina Petrova — literary reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newsppaer, author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel, and founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.