‘A textbook is not a monograph’: new approaches to school history

How school history textbooks have changed and why the role of the teacher is coming to the fore

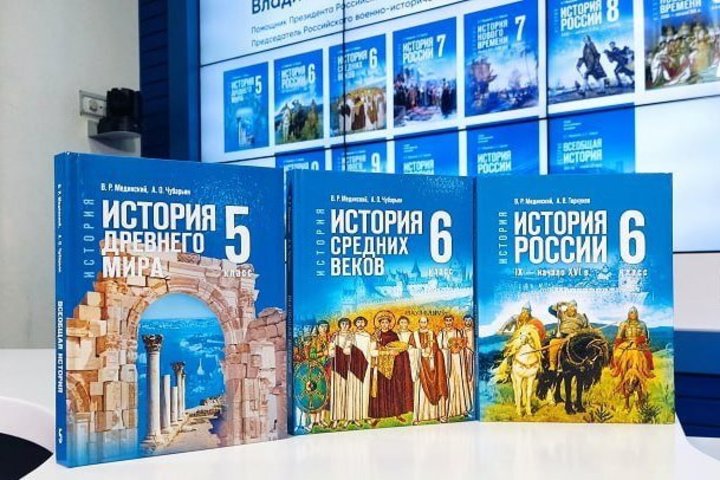

History textbooks have always been more than just books. They set the framework for national self-understanding, shaped attitudes towards the past and offered the key to understanding modernity. Alexander Chubaryan, Scientific Director of the Institute of Universal History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, told how the new textbooks differ from the old ones, how approaches to teaching history have changed and what it means for teachers.

Russian history begins with the fifth grade

One of the key changes in the teaching of history in schools is the introduction of national history already in the fifth grade. Previously, at this age, schoolchildren got acquainted only with the history of the Ancient World. Alexander Chubaryan explained that the inclusion of Russian archaeological excavations in the five-year course was an important step: “Russian history is now in the fifth grade. It was included there, bearing in mind, first of all, the archaeological excavations on the territory of our country. These are Siberia, the Volga region, ancient settlements and cities of the Black Sea region. It's in the context of ancient history, but it's now taught in the fifth grade.”

One of the most discussed issues in history teaching is the assessment of key events and personalities. Chubaryan noted that the new textbooks attempt to present modern views on Russian history: “New textbooks provide modern approaches. I would not say that we now have a complete consensus in science... But still, there is some kind of well-developed, balanced general approach.”

We are talking not only about the events of the 20th century, which have been especially actively discussed in recent years, but also about the approach to the personalities of the 18–19th centuries. For example, the image of the Russian aristocracy, which has long been portrayed in a negative way, is now viewed more objectively. At the same time, according to Chubaryan, textbooks do not pretend to be the absolute truth, which is especially important in the context of discussions around difficult periods of Russian history. As Chubaryan emphasised:

A textbook is not a monograph where authors can express any of their points of view. These textbooks are of a state nature. They have also been approved by the Ministry of Education, so there is a fairly modern common position in evaluating certain things.

Another innovation is the synchronisation of courses. Now the events of national and universal history are considered in parallel, which allows students to see the connection between what is happening in Russia and in the world: “It is very important that the events that are taught in national history coincide in time with what is going on in universal history.” For example, by studying the Time of Troubles in Russia, children simultaneously learn about the Thirty Years' War in Europe. This helps to understand that a story is not a set of individual episodes, but a single process.

“The next century will be the age of Africa”

The changes affected not only the course of national, but also universal history. Events in Asia, Africa and Latin America are now receiving more attention than before. According to Chubaryan, the compilers of the textbooks tried to “overcome a purely Eurocentric approach. We have significantly expanded coverage of events in Asia, Africa and Latin America.”

“The next century will be the century of Africa," Chubaryan confidently declared. He also noted that China, with their Confucian heritage, is a unique example of philosophical and cultural identity. India, with its growing population and importance on the world stage, also occupies an important place. Africa is seen as a region of the future, with rapid economic and cultural development. The academician stressed that understanding the peculiarities of other cultures is necessary for future personnel.

One of the trends in the new textbooks has been the attention to the history of everyday life. According to Chubaryan, world historiography is increasingly interested in topics such as nutrition, diseases, social norms and gender roles. This is reflected in school books: “We tried to expand the so-called coverage of people's daily lives in textbooks. Previously, the focus was primarily on studying abstract patterns. Now, the study of individual people and events is coming to the forefront: morals, nutrition, hunger, disease, women and men in history.”

Teacher as a source of different points of view

Despite the unification of textbooks, Chubaryan emphasises the importance of preserving the variability of views and interpretations. It is here that the role of the teacher comes to the fore, since the textbook represents exclusively the state point of view.

The teacher should present the picture more voluminously and broadly. Our children, especially adults, actively use the Internet and can find assessments that differ from the textbook. Therefore, it is important not only to present one point of view, but also to talk about another.

For example, views on the Decembrist uprising ranged from praising their exploits to criticising them as terrorists. In Soviet times, their activities were evaluated through the prism of Lenin's formula, whereas in the 1990s an alternative approach appeared. Chubaryan believes that it is important for students to understand this versatility: “It is necessary to tell children that there used to be one point of view, and now another, which takes into account that the Decembrists had certain programmes for the reconstruction of Russia.”

The Unified State Exam in History also did not go unnoticed. Chubaryan notes that recently the USE format has been refined to get away from standard formalised answers. Students now write essays similar to traditional school essays. “This will entail the need to improve the unified state exam," the academician believes. Comparing with past times, he recalled: in the Soviet school, graduates took seven state exams, including natural sciences, regardless of interests.

History of modernity: Russian Spring and SVO

One of the key topics was the presence of modern events in school textbooks. History textbooks on Russia have been updated to the present day. This decision has caused discussions, but, according to Chubaryan, it is justified.

People live in the present day, they would like to know some opinion about what is happening outside the window.

“There is a lot of interest in history today. I would say there is a boom," Chubaryan described the situation in Russia in this way. His words are confirmed by the data on a sharp increase in the number of applications to historical universities. For example, at the Russian State University for the Humanities, the historical direction remains the most popular.

The academician sees the reasons for this interest in the fact that history, like no other science, is connected with modern political processes. “History is being used very actively today," he added, noting its role in the global confrontation. However, according to Chubaryan, depoliticised science remains the ideal, although it is almost impossible to achieve this.

Ekaterina Petrova — a literary reviewer for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel, founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.