''I can't imagine how it was possible for Atatürk to rally the surviving Ottoman soldiers into the Turkish army that could successfully prosecute a war''

Oxford professor over the Ottoman Empire, major battles in WWI, Atatürk's phenomenon and Turkey's interest in the Ottoman heritage

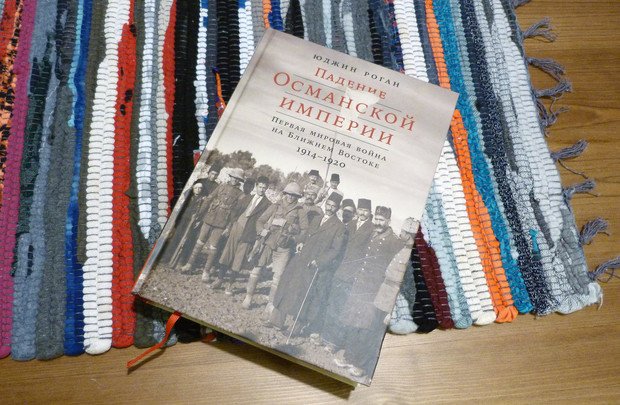

The book of historian and expert in Middle Eastern studies Eugene Rogan The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, 1914-1920 is about to come to light in Russia. In an interview with Realnoe Vremya's reporter, the Oxford professor, expert in Modern Middle Eastern History tells about the Ottoman Empire, major battles in WWI, Atatürk's phenomenon and Turkey's interest in the Ottoman heritage.

''It wasn't sure whether I was going to be a businessman like my father or a diplomat or a journalist''

Mr Rogan, first of all, could you tell our readers about yourself?

I was born in the United States. My father worked in the Arab space industry. When I was 6 years old, we left California to move to France. We lived in Paris for two years and then moved to Rome for a couple of years. When the government of Saudi Arabia approached the United States to acquire Northrop air planes for their air force, my father was sent to open a Middle East office for Northrop. That's how we got to the Middle East. I got to Beirut when I was 10 years old, at the beginning of 1971, and we lived there for five years until the civil war became entrenched. We left Beirut at the end of 1975 and moved to Cairo. I finished my school in Cairo. Those 8 years in the Middle East were just the years when as a young man I was gaining consciousness of politics, what's going on in the world, around me. I think it made the Middle East more interesting to me than any other part of the world. I finished school in Cairo and was back to the United States to study at university. I did a Degree in Economics at Columbia and then decided to study the Middle East because I was thinking I would have a career in the Middle East and went Harvard to do a degree in Middle Eastern Studies. That's how I began to read history for the first time and I loved it.

So was it your childhood in the Middle East that influenced your choice of profession?

It wasn't sure whether I was going to be a businessman like my father or a diplomat or a journalist. But at Harvard, as I said I began to really study history for the first time. In the end, I became a scholar, I stayed at university, I did a PhD in History. When I finished my PhD, I applied for jobs to be a professor and I was fortunate enough to be hired by Oxford. I left America again. I came here in 1991, so I've been for 26 years now. From here, I have the opportunity to travel widely across the region, do my research and teaching. I've written not only The Fall of the Ottomans but my earlier book called The Arabs: A History that Alpina will publish in a year or so. It will be a large history of five centuries of the Arab world.

When nationalism wins imperialism

Your book titled The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, 1914-1920 is being prepared for publication in Russia now. Do you think that the Tripartite Alliance consisting of Germany, Austria, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria had a chance to win?

I think that the Tripartite Alliance had a chance to win until the very last days of the war. It was never clear who would actually win WWI until finally in 1918 the war came to an end. And I think the really decisive fact was that industrial powers such as the United States entered the war and began to conscript in such numbers that it really shifted the strategic balance in favour of the Triple Entente. But until that point, every army in the great war had legitimate grounds to believe they could win the war or lose the war.

I've written not only The Fall of the Ottomans but my earlier book called The Arabs: A History that Alpina will publish in a year or so. Photo: cont.ws

Why did the Ottomans choose the Germany's side?

Well, in my book I make the case the Ottomans would have ideally preferred to have stayed out of the war. They feared for the Russian intentions on Ottoman territory, specifically that Russia would take advantage of the general European conflict to secure its long-standing historic aspirations over Constantinople and the straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. These were policy decisions that had been taken by the tsarist government already at the beginning of 1914. And what really motivates the Ottomans is to try and secure a defensive treaty of alliance, to protect their territory from their Russian neighbours against whom they'd lost so many wars in the recent past. And in that sense, because Britain and France were already in alliance with Russia, it was inconceivable they would enter into a defensive treaty with the Ottomans protecting the Ottomans against Russia. Germany stood out as an industrially advanced, militarily strong power with no defined interests in the Ottoman Empire. This fact made Germany the inevitable choice for the Ottomans.

What did they lose?

In making the choice, the Ottomans secured their ally that provided them with state-of-the-art war technology and allowed them to defend their territory successfully for four years. They also seem to have come through the war. There was at least within Turkey still a drive to realise their own aspirations of self-determination. When they defeated the Ottoman Empire, instead of ending Turkish national aspirations, it led to a break between the Turkish national movement led by Mustafa Kemal and the Ottoman government in Constantinople. And that will ultimately lead to a fall of the Ottomans, not at the hands of the victorious European powers but at the hands of the Turkish national movement, which in defeating the French, Greek and Italian armies in Anatolia was also able to overturn the rule of the Ottomans and establish the Turkish Republic under Mustafa Kemal's presidency.

''There was a sense among the soldiers themselves they were defending homeland''

Why do you think they managed to conserve their independence after WWI?

It's a really good question. I can't imagine how it was possible for Mustafa Kemal to rally the surviving Ottoman soldiers into the Turkish army that could successfully prosecute a war when the Ottomans had been losing wars since 1911. They must have been the most war-weary nation in the world by 1920. It's hard for me to understand what might have driven their nationalist drive to make one more war and to win that war. But I think that here it really comes down to the unwillingness of Anatolian Turks to accept defeat and to surrender their territory to the Greeks, in particular, a country they had long-standing antagonism to it. And they were never seen frightened up. They've always seen Greece as a smaller country that in the normal order of things Turkey should defeat. It might have made psychologically easier for the Turks to fight against the Greeks – a long-standing hatred and a sense of superiority. For instance, they've always had some inferiority complex and always felt the weaker power against Russia or Britain or France. I think it's psychological and hypothetical explanations. As a historian, all I can say is it is remarkable that the Turks were able to come out of defeat in WWI and rally for one more conflict to consolidate the territory of Turkey and to realise their own national aspirations.

Does the key role belong to the phenomenon of Atatürk?

We all try and avoid explaining major historical events in terms of а great man. And I'd say that Atatürk was certainly an essential leader. But he was not the only leader. He was surrounded by other nationalistic ideologues who were determined to preserve Anatolian Turkey from foreign occupation. I think also there was a sense among the soldiers themselves who fought defending homeland in a way which has always motivated peoples to fight. So they had the motive. If you think about every country that comes under foreign occupation or foreign invasion, how people have a motive to defend their land. They had experience in armed forces training. Many of them served in the military, and they had experienced soldiers. They had weapons left over from WWI. And they had a leader. I think all these factors explain why the common Turkish soldiers led by a man like Atatürk and his generals were able to prosecute a war. It's more than one man, it's a nation.

I'd say that Atatürk was certainly an essential leader. But he was not the only leader. He was surrounded by other nationalistic ideologues who were determined to preserve Anatolian Turkey from foreign occupation. Photo: culturelandshaft.wordpress.com

''The expectation that colonial Muslims would respond in the kind of fanatical way reflects more the fears of European Orientalists than the reality of Muslims''

Let's switch to another aspect covered in your book. Why did the rise of Muslims in colonial countries of the Triple Entente fail?

I think it's not surprising that you didn't have major uprisings among colonial Muslims because, in a sense of livelihoods, you're not being directly threatened. Can you expect the major uprisings to happen on rational grounds? They are living under their own constraints and conditions, they concerned about their livelihoods, they tried to make a living, they try to provide for their families. Where in those priorities does the kind of religious fanaticism play a role? As long as British did nothing which offended Muslims and stability in India itself, there'd be very little ground, however much sympathy Indian Muslims might have for the Ottoman Empire to risk their life and their welfare, to answer to a foreign leader's call. Even if they recognised that foreign leader had some spiritual authority over the world's Muslims. You know, I think in a sense the expectation that colonial Muslims would respond in the kind of fanatical way reflects more the fears of European Orientalists than the reality of Muslims living under the colonial occupation.

Why didn't the captive Muslims join Ottoman forces?

I think there were colonial Muslim soldiers imprisoned by the Germans who did join Ottoman forces. In my research, I found references to as many as 3-4,000 soldiers were recruited from Halbmondlager, which is a prisoner-of-war camp created specifically for colonial Muslim soldiers. We know they were sent to fight in Baghdad and Persia. I even found references to some Algerian colonial soldiers being sent to fight to Hijaz war against the Arabs. I don't think their war experience was very easy one. I don't think that they were convinced to join the Ottoman army. For many of them, it was probably very difficult service. Still, it was someone else's war. They were not fighting to protect Africa, they were not fighting to protect their families. They were finding themselves to be sent to very remote frontiers to fight against people they had no enmity towards on behalf of people they didn't know in the Ottoman authorities.

As far as it's known, Muslim ethnic groups, particularly Tatars, fought in the Russian army. How did they prove themselves on the Turkish front?

I don't know the answer to that question. What I'd say is as an author I was most disappointed in not having more material to provide information from the Russian side of the trenches. I'm very excited that my book is being translated into Russian and I look forward to getting responses from Russian readers. I'd be very curious to know whether in Russia there's been the publication of diaries and memoirs of soldiers and officers from WWI particularly those who fought on the Ottoman front. It would be a very exciting addition to our understanding of the world in the world war.

If you look at my footnotes, you will see what sources I use. The most recent work has been Sean McMeekin's study of Russia and origins of the First World War, which is very unsympathetic to Russia, basically wants to blame Russia for WWI. But he has Russian language skills and sights and sources he had consulted in Russian archives. So that was useful to me. I admit that there is so much more to be done on Russia's experience. I hope that this research is coming out in Russia and that somebody will translate it for the benefit of English readers.

Did you read all material in Turkish?

Having studied Arabic, the pathway to Osmanlıca is much easier, and writing is not a difficulty – there are many Arabic words still in Turkish. But the challenge for foreigners and I think for Turks is the complexity of Turkish syntax, particularly in Ottoman Turkish. It's so difficult to break the text into small sentences because Ottoman Turkish is written as one great continuous paragraph. For my sources, I was relying mostly on the diaries of soldiers, those that have been published. The language is actually quite simple — soldiers don't tend to use a very elaborate language, it's very simple phrases. These were books that have been published by İş Bankası, Kültür Yayınları — a whole series of diaries and memoirs that have been really useful in my work. Otherwise, it was material that I had been gathering for previous projects — I had some material that came from Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri drawing on the interior ministry's reports, I had some Ottoman document resources.

I think the Turks really wish to remind the world that their performance in WWI was marked by many important victories before the ultimate defeat. Photo: oper-1974.livejournal.com

''Turkey has no scope for imperialism''

The war precisely on the Turkish front in WWI is badly covered in Russia. What are the most interesting episodes in these fights?

In my book the episode that I focus on most was, of course, the Battle of Sarıkamış, which is right at the beginning of the war when one of the leading young Turk rulers Enver Paşa launches a surprise attack on the Russian Caucasus Army at the railhead of Sarıkamış hoping to encircle them in imitation of what Germany had done to Russian armies at Tannenberg. And he leads his very best soldiers to a terrible death in desperately cold conditions in the high mountains in deep snow conditions. Here again, I was reliant on the work of western authors writing on the Russian experience. I had no first-hand accounts by Russian sources about their experience of the Sarıkamış battle. And the other instance, of course, is the spring initiative in 1916 against Erzurum in which tsarist forces succeed in conquering what was deemed to be an impregnable fortress city in Erzurum. They will continue their conquest heading west from there, up to the Black Sea, to secure a very large part of north-eastern Turkey under Russian rule before the revolution.

Can you name the key battles in this direction?

Besides the Erzurum Campaign, the capture of Trabzon – Trabzon fell without a major battle – on the opening days of the war, there was an initiative in Köprüköy in which Russia secured a buffer zone. It's not a major battle in the sense that the Ottomans are forced back 30 km or so but the whole length of their frontier. It's where Enver will launch his attack on Sarıkamış. After that, you obviously have the Russian invasion of Van that led to the Armenian genocide. They are certainly major battles that take place in Van – that's covered in the book as well. I think Russian and Ottoman forces were engaged in Persian territory. I'm going to be very open with you and say that all of the fronts in the Ottoman experience of the war, the one in which I had the least regional material was certainly would be the Russian front. Some Ottoman memoirs are fighting in the Caucasus region and help get the Ottoman side of the story. But I would be very interested to know more about the Russian experience, their fight with the Ottoman Empire.

Now the Ottoman heritage is very popular in Turkey: for instance, Abdul Hamid is glorified, the Battle of Gallipoli and other fights are remembered. What is it, in your opinion? Is it a sign that Turkey is embarking upon a path of imperialism?

I think Turkey has no scope for imperialism. I don't think there is any way that Turkey can extend its influence. The areas where you see Turkey going beyond the zone of frontiers have to do with ongoing antagonism with the Kurdish movement. But I don't think Turkey has any interest in trying to extend a permanent presence in Syria. And certainly what it doesn't want Iraq and Kurdistan to declare its independence. Nor does Turkey wish to extend its military into Iraq. All countries will try and use history as a way to promote the government and power and make citizens feel pride and the glory of the nation's past. We see in the WWI remembrances, each country celebrating their victories and remembering their losses and defeats, and what's been a very painful process for Germans, French, Britons, Russians. I think the Turks really wish to remind the world that their performance in WWI was marked by many important victories before the ultimate defeat. The government in remembering Ottoman victories does try and enhance its own legitimacy is not particular to Turkey but it's a little bit ironic.

Obviously, this government has tried to distance itself from the legacy of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. They try to undo the secular reforms that Atatürk had imposed on Turkey as a modern nation-state. I think they had very ambiguous relationship with the legacy of Mustafa Kemal. So the question of how they remembered Galipolli was slightly troubled by that contradiction. On the other hand, it explains why Erdoğan's government was so proud to celebrate the victory over the British in Kut-al Amara in 2016. It was a battle they won against the British without Atatürk's involvement and was one that the Erdoğan government was really keen to try and appropriate. To me, it's just politics, trying to take advantage of history.